The Auburn Emporium – Auburn, NSW

Let’s take another trip to that seemingly bottomless well of source material, Parramatta Road. If this Australian Women’s Weekly logo looks ancient to you, that’s because it is. In fact, I’d say there’s a good chance the magazine itself sported this logo the last time it was on sale at this location, which was most recently known as Danny’s Newsagency. But what’s happened to the sign there?

Oh, well this changes everything. Before Danny moved in, the newsagency was Brown’s domain. Perhaps the AWW sign belonged to Brown in the first place. Case closed, unless the awning offers us any more clues…

No. It was Brown’s Newsagency, then Danny’s, and now it’s a freight company called BLM, which is apparently just too busy to take down some old, misleading signs. Mission accomplished, what a great story, we can all go home. Was it good for you too? Seriously, why can’t these shops just present a decent front? If BLM wanted more business, why wouldn’t they dust themselves off a bit (unless they don’t want more business ON PURPOSE)? Does the rest of this row of shops have the same issue?

No. It was Brown’s Newsagency, then Danny’s, and now it’s a freight company called BLM, which is apparently just too busy to take down some old, misleading signs. Mission accomplished, what a great story, we can all go home. Was it good for you too? Seriously, why can’t these shops just present a decent front? If BLM wanted more business, why wouldn’t they dust themselves off a bit (unless they don’t want more business ON PURPOSE)? Does the rest of this row of shops have the same issue?

On the east corner we’ve got Blossoms wholesalers of health, beauty and ugg. Great combo. Looks like they ran out of yellow paint before they could disguise the fact the place used to sell:

..’beding’, among other things. Great. What’s that up there?

You can’t have freezers without fridges. Oh look, the building was finished in 1912. I bet they weren’t this lazy or negligent back then. Next…

The next door down offers no such insights – it’s a boring restaurant. Beside that, it’s this accountant. And a pretty busy one right now I’m sure, given what time of the year it is. Yawn…I’d imagine this place wasn’t so pedestrian in 1912, a time when Parramatta Road wasn’t a huge embarrassment to the city and a great place to park your car on weekends. It would have had a purpose, it would have been the product of some dude’s life’s work. It would have stood out from the crowd and meant something rather than just taken up space with its ugliness.

The next door down offers no such insights – it’s a boring restaurant. Beside that, it’s this accountant. And a pretty busy one right now I’m sure, given what time of the year it is. Yawn…I’d imagine this place wasn’t so pedestrian in 1912, a time when Parramatta Road wasn’t a huge embarrassment to the city and a great place to park your car on weekends. It would have had a purpose, it would have been the product of some dude’s life’s work. It would have stood out from the crowd and meant something rather than just taken up space with its ugliness.

Yeah, I’d like to think this was something really special…back in the day…

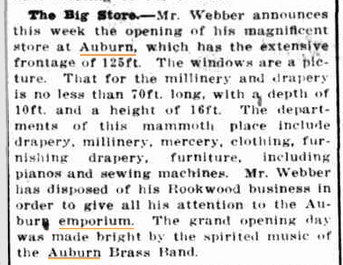

Mr. Webber had sold his other business at nearby Rookwood, presumably the one on which he had built his name, because he had such faith in this place. Wow. “The windows are a picture.” Wow! They sold pianos and had the Auburn Brass Band on site to celebrate the opening. It’s hard to believe that such an event could once have gone on at this place we’ve seen today, but there you go.

Don’t let anyone tell you department stores aren’t a cut-throat (or cut-head, in this case) industry, just like I won’t let anyone tell me that Wylie’s departure from Webber’s empire and Arthur Webber’s injury are just a coincidence. In fact, let’s concentrate on Wylie’s little advertisement for a moment. First, he’s taken it out in the accidents section of the paper, which doesn’t bode well. Second, he’s done it directly below an account of his former employer’s misfortune. Third, he’s included the snide ‘up-to-date Store’ dig, as well as imploring thrifty shoppers to ‘compare his prices’ (to whom, I wonder?)…and yet the very next line tells you there’s one one price to compare. In case you’re interested, his address is a Westpac bank today, which means this paragraph is his legacy. Suck it down, Wylie.

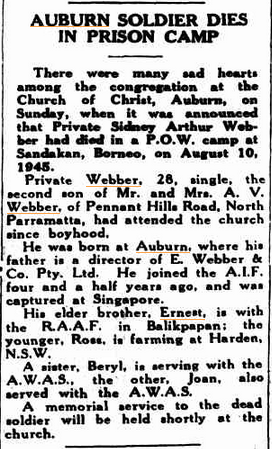

Gee, the Webbers seem a little…accident-prone, don’t they? In 1921 young Ernest Webber (son of Arthur) cut his finger. And it made the paper. Slow news year, perhaps?

So successful was the Webber store that a Mrs. Middleton took the fight to Merrylands. I wonder how it turned out?

Ernest E. Webber (who I’m assuming isn’t the seven-year-old with a bandaid on his finger) copped a heavy fine of four pounds for not paying two of his employees the minimum wage. No wonder Wylie left. Shoulda just paid ’em, Ernie.

Just don’t expect minimum wage. Hey, what a deal there at the top: a set of teeth from one guinea. Yuck.

The Webbers, still in PR crisis mode, provide the furnishings to a local recital. We haven’t forgotten about the third world wages, Ern.

And neither has Desire La Court (what a name). Read that thrilling tale of escape in the third paragraph, and tell me it wouldn’t make a great white-knuckle thriller starring Channing Tatum.

Here’s Webber’s castle, paid for by the unpaid wages of his workers.

I can’t decide whether my favourite part of this story is the thief begging Webber not to call the cops and then offering to drive Webber to the police station, or him playing the ‘my wife and kids’ card for sympathy and later denying having done so. It’s just a quilt, Webber. Even if he did nick it, let him have it. The Depression’s coming.

And now they know: don’t throw a lit cigarette onto piles of paper.

Good thing they advertised this, now all the thieves out there with a copy of the 1927 paper and a map will know his house is empty.

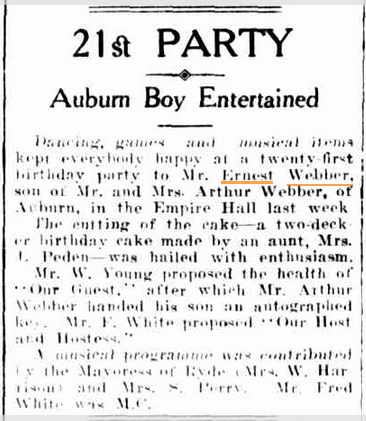

Young Ernest Webber, last seen blubbering like a baby over a cut finger, has turned 21. Lock up your daughters! Nice cheapskate present, Dad – an autographed key. “My signature will be worth a lot of money in a few years, son…”

Do you think Mark Foy was this plagued by thievery?

This plagued? This seems just a little suss, don’t you think?

The plot thickens. I like the use of quotation marks around “square”, as if to square this divorce meant some drastic action.

And finally the truth comes out! Picture the headlines: “Webber of Deceit”. I wonder if Webber’s trip to Jervis Bay was advertised in the paper? Maybe all those other times Webber was thieved from was the result of some cuckolding. I can only imagine how his wife must have felt…

Oh.

From philandery to philanthropy. Wisely replacing the adulterous E. Webber as media spokesperson, Arthur Webber sets off on his quest to repair the Webber reputation, 150 shoppers at a time. I’m guessing they had a sign, “Toilet and air-raid shelter for customers only.”

With the war over, the Webbers put some distance between the scandals and tragedies of the past by backing the Auburn ‘Popular Girl’ Competition. Really rolls off the tongue, doesn’t it? You’re pretty much asking for trouble inviting someone named ‘Mrs. Crooks’ to your fancy ball, especially given your history, Webbers.

Sadly, this grand event is where the Webber story comes to an end. The trail went cold, and nothing more hit the papers. But despite the abrupt and mysterious ending it kind of feels like we were right there with them…almost like we were one of them. Do we need to know what happens next? Do we need the sad details of the day the Webbers signed their pride and joy over to Brown of Brown’s Newsagency? Of the day one of the shops was demolished to make room for Gypsy Leather, ruining the established style? Probably not. The best years are behind us at this point, and we’ve only the advent of Danny’s Newsagency to look forward to. We can use our imaginations to fill in the blanks.

Plus it’s been an adventure. We’ve laughed, we’ve cried, we’ve been scandalised and burglarised, but above all, we’ll never look at this innocuous little row of shops with the same eyes again. Right? Here it is again, just to be sure:

Devonshire Street Cemetery/Central Station – Sydney, NSW

“I once walked through the burial grounds on the Surry Hills, in the commencement of Spring, just as the flowers were beginning to bloom forth in all their beauty…”

Bridget Flood was in the same situation too many of us have found ourselves in all too often: stranded at Sydney’s Central train station, hopelessly late. The big difference is that she was waiting there for over 60 years.

As we’ve previously learned, 1820 was a good year to die in Sydney. Rather than ending up beneath the public piss-pot that was once the colony’s first burial ground, you could find yourself in a brand new plot freshly dug at the just-consecrated Devonshire Street Cemetery.

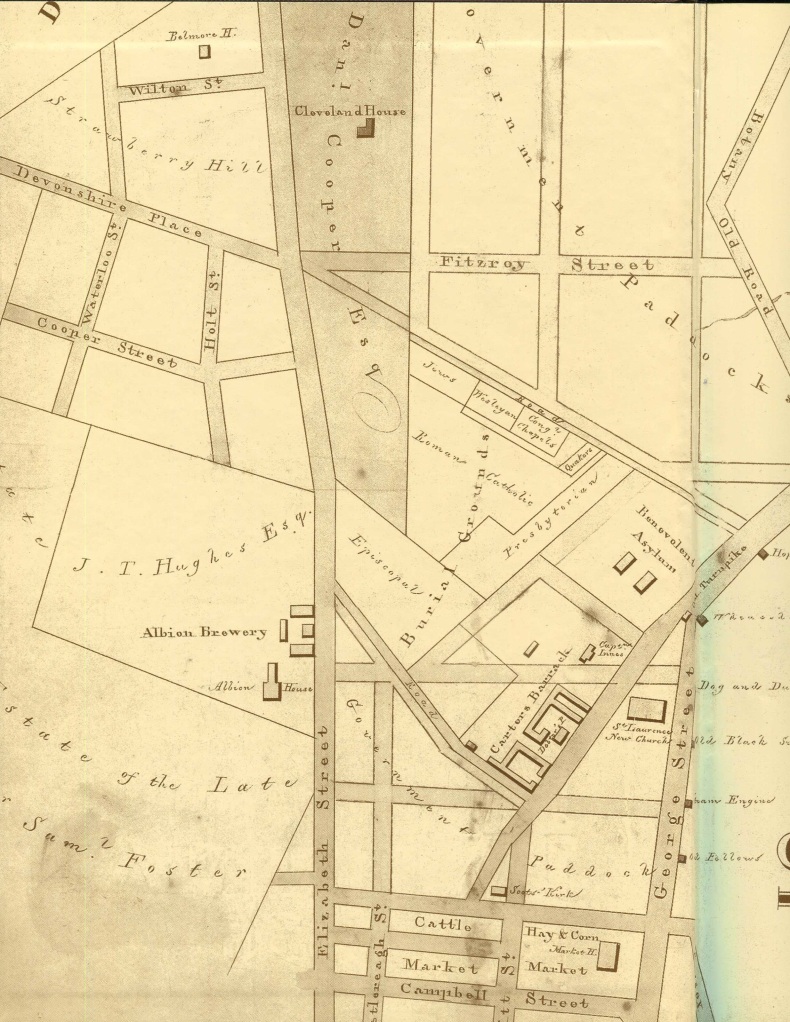

Chosen for its abundance of space and central (heh) location, the area bordered by Elizabeth and Devonshire streets was chosen to replace the Old Burial Ground as Sydney’s premier final resting place. Quartermaster Hugh McDonald, 40, was the first lucky stiff to be buried there following his death in 1819. Long waiting lists…so Sydney so chic.

“It was early in the morning when I commenced rambling amongst the tombs, the dew had not yet been dissipated by the genial rays of the invigorating luminary, and the cool fragrance of the atmosphere had not yet given way to the noon-day heat…”

Bridget Flood died in October 1836 at the age of 49 and, like virtually all deaths in Sydney at the time, was interred at the Devonshire Street site. Quoth her headstone:

“Pain was my potion

Physic was my food

Groans were my devotion

Drugs did me no good

Christ was my physician

Knew what way was best

To ease me of my pain

He took my soul to rest.”

They don’t write ’em like that anymore. And rest she did, as did all those buried at Devonshire Street Cemetery well past its 1867 closure.

Although steadily employed by the city’s dead between 1820 and 1866, the nail in the coffin (heh heh) for the cemetery was the latter year’s introduction of the Sydney Burial Grounds Act (NSW), which prohibited burials “within the city of Sydney from 1 January 1867, with the exception that persons with exclusive rights of burial at that date could still be buried on application to the Colonial Secretary who needed to be satisfied that ‘the exercise of such right will not be injurious to health’“. Phew. Just tie some rocks to me and throw me in the harbour!

You’d think this act would be in anticipation of some kind of grand plan for the burial ground, but no. With the exception of infrequent additions to family plots as outlined by the overly wordy act (and even these ceased in 1888), Devonshire Street was largely ignored by the growing city while new sites like Waverley Cemetery and the Rookwood Necropolis served the public’s burial needs.

Prince Alfred Park’s Exhibition Building looms large. Devonshire Street Cemetery, 1901. Image courtesy Royal Australian Historical Society.

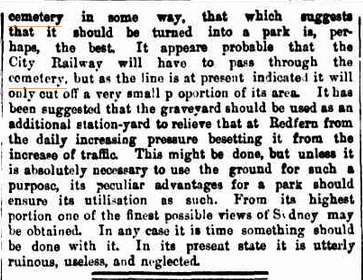

By 1900, its advanced state of neglect and decay reflected its residents and disturbed the public:

…although it wasn’t all bad:

“In short, it was exactly such an hour as an imaginative or sensitive being would delight to rove about, and lose himself in the regions of fancy…”

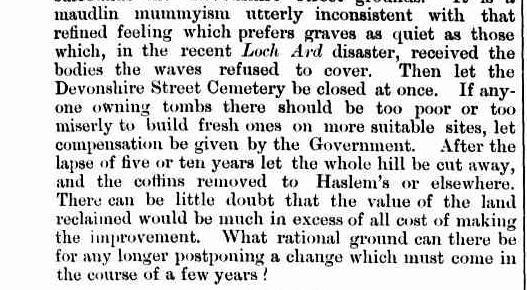

It wasn’t long before some of the more opportunistic voices began to speak out about the the site’s real estate value:

And as early as 1888 there were rumblings about how best to use the land:

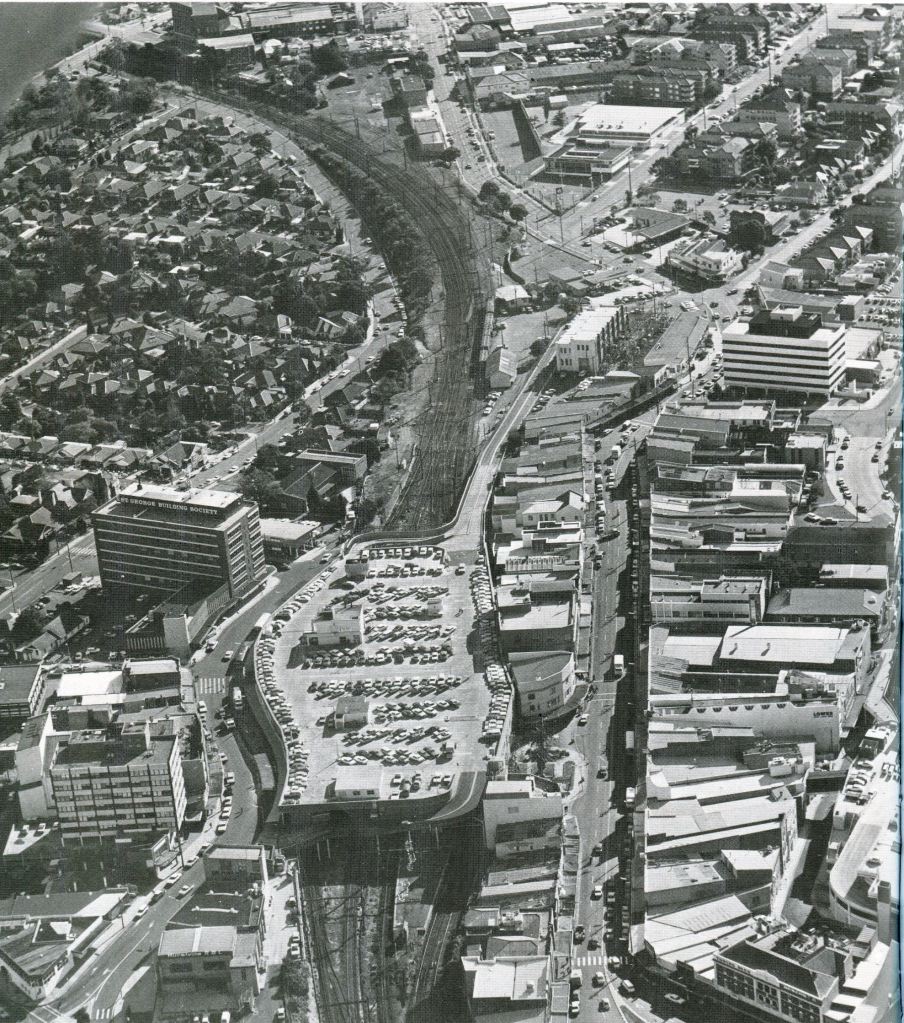

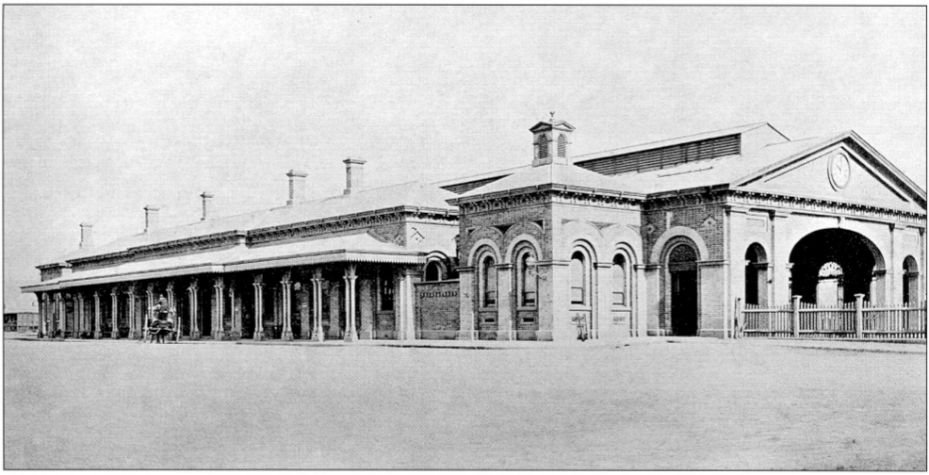

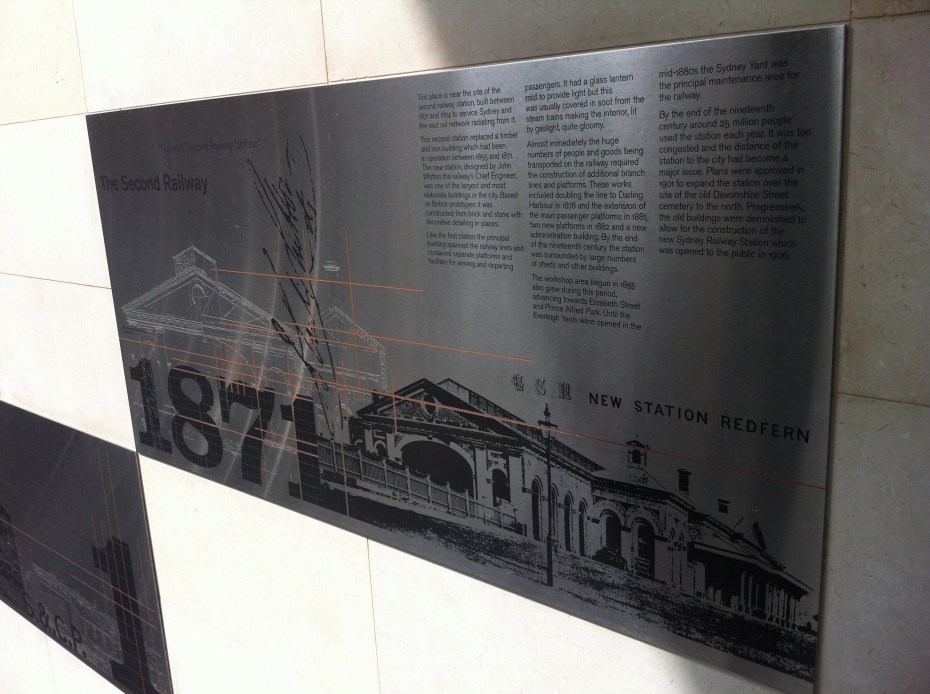

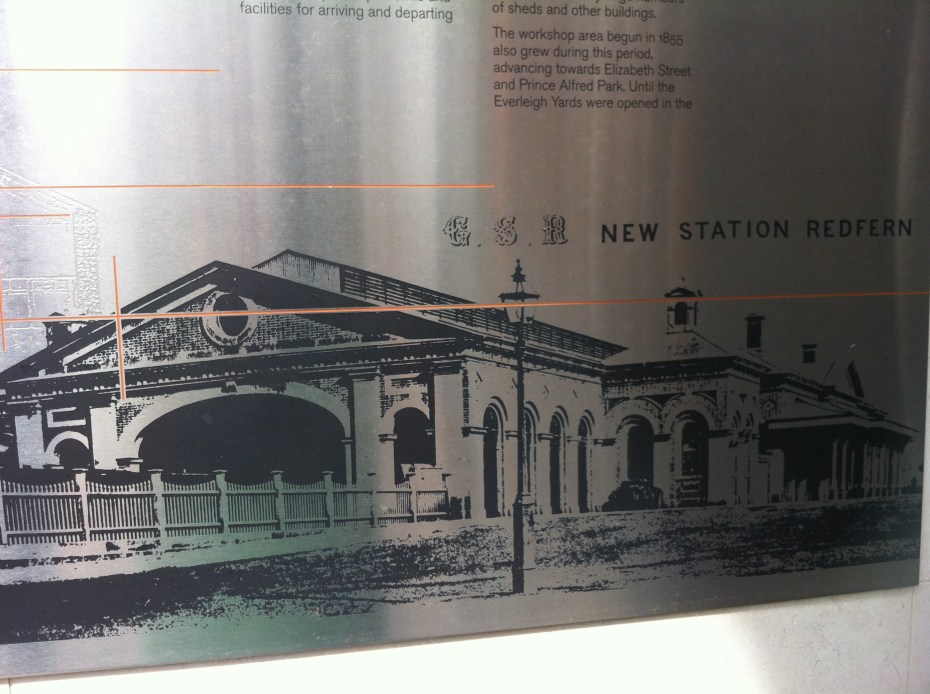

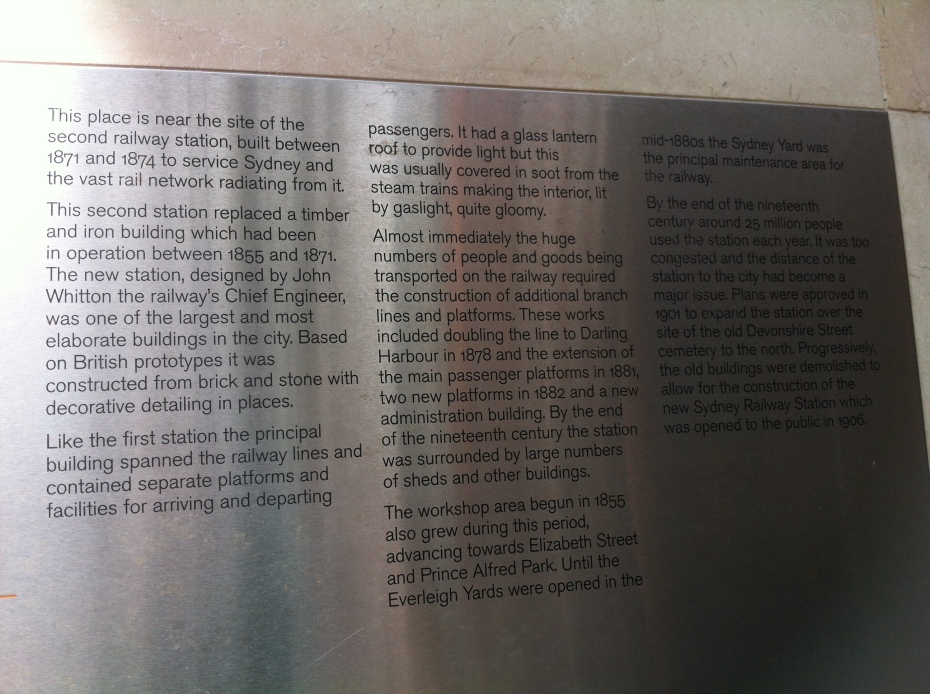

It made sense, given that Central Station’s predecessor, ‘Sydney Station’, lay opposite the cemetery along Devonshire Street.

Since 1884, Sydney’s existing rail network had been under the stress of increasing traffic and a limited reach (sounds familiar, doesn’t it?). Sydney Station was constantly receiving upgrades and additional platforms, culminating in a messy setup of 13 train platforms and numerous tram sheds (sounds familiar, doesn’t it?). The city’s railway commissioners initially struggled to decide upon a plan for the future which would provide Sydney with a central hub expansive enough to extend the rail network to the suburbs (sounds- never mind).

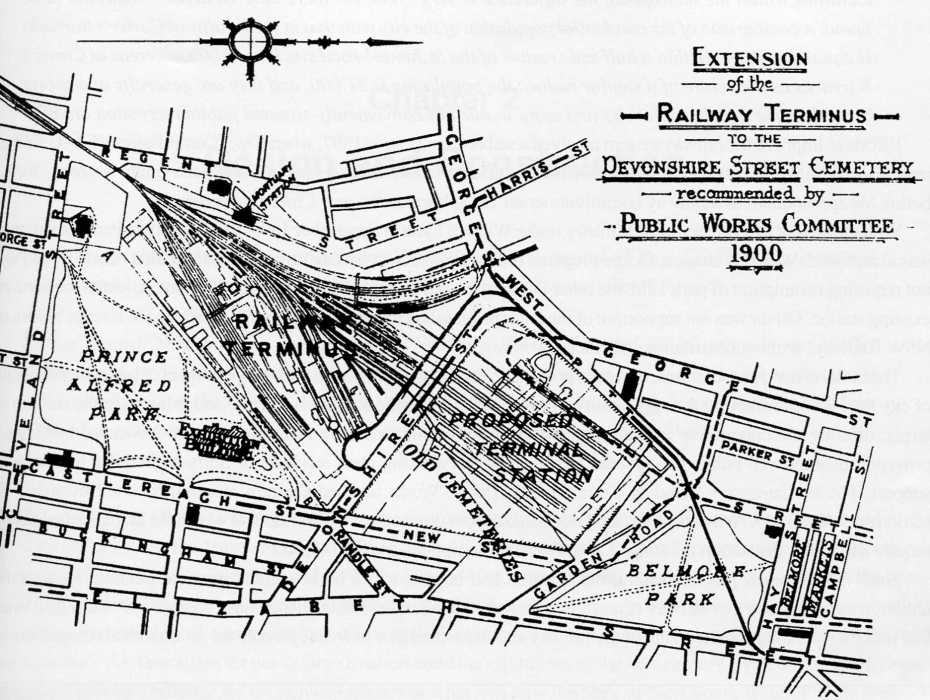

An 1897 royal commission proposed the resumption of Hyde Park for use as the central terminal and, to counter the public outrage over the loss of parkland, the Devonshire Street Cemetery would be converted into a park. For a time this plan seemed to be a go until the unexpected death of Railway Commissioner E M G Eddy (of Eddy Avenue fame) that same year. This forced a literal return to the drawing board, where it was decided that it was probably easier to resume just one giant park instead of two. Nice thinking, guys.

In January 1901, the Department of Public Works served notice that anyone with relatives buried at Devonshire Street were to front up and make known their desire to have the remains reinterred at other cemeteries by train, with the cost to be borne by the NSW Government. These days, they’d just tell you to bring a shovel.

Unfortunately, these relatives were given a strict time limit of two months to act, and by the end of that time, only 8,460 bodies had been claimed (not among these was Eddy, who had been buried at Waverley following his death). This left 30,000 remains unclaimed, most of which were transferred to other cemeteries anyway, but due to the rushed nature of construction and given they did such a bang-up job the last time, it’s safe to say there are more than a few commuters at Central waiting for a train that will never come.

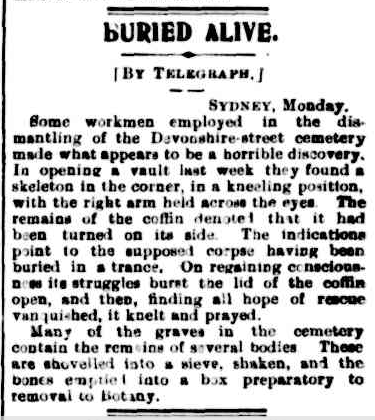

With that many bodies to exhume, you can imagine just how many creepy stories must have come out of the venture. Here’s just one:

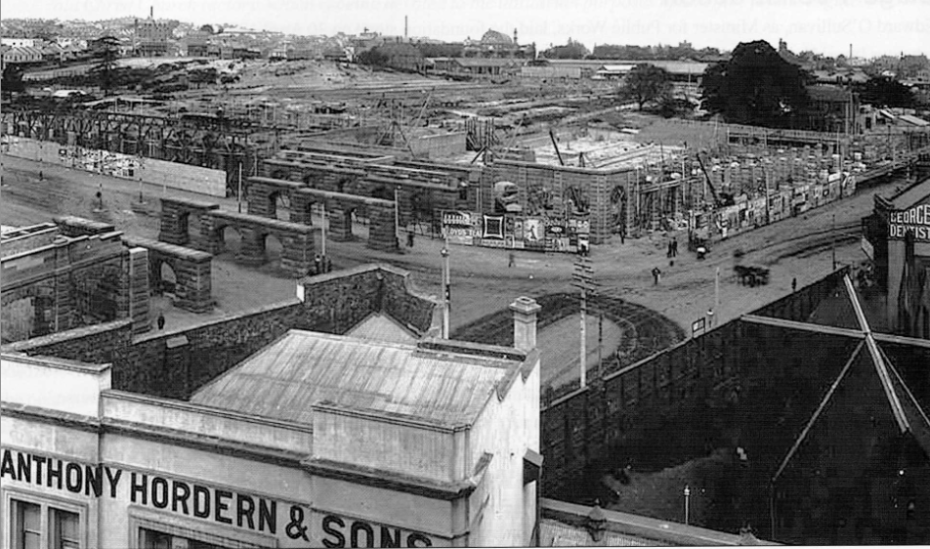

The reason for the rush was that Melbourne had started work on their Central equivalent, Flinders Street Station, that same year. Sydney was determined to get the drop on Melbourne this time, as Flinders predecessor ‘Melbourne Terminus’ had been Australia’s first city railway station back in 1854, pipping Sydney by a year. The Devonshire Cemetery site had been completely cleared by 1902, and stage one of Central’s construction, which aimed to have the station operational, was completed in 1906. On opening day, the new station featured…13 platforms. Despite being twice the size of its predecessor, this was no improvement, and did nothing to alleviate Sydney’s transport woes (but then again, what ever does?).

“I directed my footsteps to a cluster of tombs on an eminence, which was thickly covered with green and blooming geraniums…”

But the unexpected fruit of the Department of Public Works’ labour was the emergence of commercial activity in the areas surrounding the new station. Its proximity to the city made department store shopping for those out in the sticks a treat, with Grace Bros., Marcus Clark, Anthony Hordern, Bon Marche and Mark Foy all within walking distance of Central by 1908. The Tivoli and Capitol theatres became entertainment meccas for those starved of entertainment in the ‘burbs.

Anthony Hordern awaits new business during Central’s construction, April 1903. Image courtesy ARHS Rail Resource Centre.

The station itself was hardly the thing of beauty its early designs had suggested, with the rushed development cycle omitting many intended features – least of all Central’s iconic clock tower, which wasn’t completed until 1924.

The construction wasn’t just focused on making sure the station would be operational before Flinders Street, though; there was particular care taken to ensure no trace of the Devonshire Street Cemetery remained, going so far as to completely eradicate Devonshire Street west of its intersection with Elizabeth. Other structures that once stood on the land now occupied by Central and its surrounds – the Belmore Police Barracks, the Benevolent Asylum, the womens refuge – have similarly been lost to time.

“I at first almost forgot the ravages of the grave in contemplating the enchanting appearance of the place.” – James Martin, 1838.

Today, nothing remains to remind commuters of the morbid nature of Central’s past. The cemetery itself was largely situated underneath today’s platforms:

Devonshire Street Tunnel, once Devonshire Street, runs directly underneath the path once carved between the cemetery and Sydney Station, depositing Surry Hills pedestrians into Railway Square amid el-cheapo bargain shops, youth hostels and fast food joints.

Also in Railway Square is a series of plaques designed to inform passers-by on the history of Central Station and railway in NSW. The cemetery is mentioned in passing (heh).

The uneven terrain of Belmore Park perhaps provides us with the nearest idea of what the Devonshire Street Cemetery was like in its natural state as is possible today, although even it has a sordid and ugly past as an open gutter for the refuse of the nearby Belmore Produce Markets and Paddys Markets.

Rookwood Necropolis, Eastern Suburbs Memorial Park, Woronora Cemetery and many others were the recipients of many of the (not so) permanent residents of Devonshire Street, but none feature as striking and immediate a memorial as the tiny, eerie Camperdown Memorial Rest Park. Here, amongst the sombre atmosphere of tombstones and gloomy, gnarled trees lie what were once the gate posts met by visitors to Devonshire Street. These were removed along with everything else in 1901, and mysteriously disappeared from existence until 1946, when…

It seems almost sacrilegious that thousands of commuters tread all over this once-consecrated ground every day without any kind of marker to signify what was and who mattered, even if it was nearly 200 years ago. C’mon, NSW Government! They’re even in the right electorate! Meanwhile, to the 30,000 Sydneysiders scattered to the four corners by the winds of progress, the term ‘final resting place’ has little meaning.

Finally, here’s a fascinating account of a visit to Devonshire Street Cemetery just as its demolition was beginning. It originally appeared in the Clarence and Richmond Examiner, October 1 1901.