Past/Lives Flashback #8: Sydney Olympic Park – Homebush, NSW

Original article: NSW State Abattoirs/Sydney Olympic Park – Homebush, NSW

It’s hard to believe it’s been a year since I last visited this place. The blood-soaked history of Sydney Olympic Park is perhaps the most heavily researched article on Past/Lives, yet all that knowledge is quick to fall away when you’re actually standing on site, inhabiting the space where it all went down. The post-Easter Show cleanup only serves to strip back the gaudy decorations designed to distract from the past, leaving today’s visitors with one of two visions: the glorious Olympics, or the violent abattoirs.

It’s hard to believe it’s been a year since I last visited this place. The blood-soaked history of Sydney Olympic Park is perhaps the most heavily researched article on Past/Lives, yet all that knowledge is quick to fall away when you’re actually standing on site, inhabiting the space where it all went down. The post-Easter Show cleanup only serves to strip back the gaudy decorations designed to distract from the past, leaving today’s visitors with one of two visions: the glorious Olympics, or the violent abattoirs.

Apart from the hubbub surrounding the Easter Show, change visits the Olympic zone about as often as I do (read: not much). The stadium seems to have settled on ANZ as its name for the time being, just as the arena’s heart still belongs to Allphones. During my refresher course on the ins and outs of the Olympic era of the site’s history, I laughed when I learned the arena’s actual name is the ‘Sydney Super Dome’. For the first time ever, Allphones sounds comparatively low-key.

So since change is such a stranger here, it’s going to be more beneficial to take a look at some of the landmarks around the Olympic site that betray its brutal past. We didn’t touch on too many last time, with the Abattoir Heritage Precinct being the natural focus. First up is Olympic Park station, the last stop of the train line which delivers thousands of Easter Show-goers to the park each year…

…just as it delivered hundreds of thousands of animals to their deaths each year for decades, some as recently as 25 years ago. Granted, it isn’t the exact same station (although if it was, abattoir workers would have enjoyed the most stylish station in Sydney), but its location is approximate to the original. A complete train line (with stations opening from 1915) served the abattoir and the nearby brickworks, with country trains deviating from the existing rail network at Lidcombe and Flemington to deposit country animals to the abattoir. Employees could catch their own trains from a small platform at the end of Pippita Street, Lidcombe.

As the abattoir declined, the need for employees did so as well, and in 1984 the abattoir line was closed, with the facility itself closing in 1988. The entire Homebush Salesyard Loop, on which the Olympic Park line is based, was closed in 1991. In 1996, the Pippita Street station became the last of the abattoir stations to be demolished, and interestingly, the street itself was absorbed into the huge Dairy Farmers site nearby (now, why do you think that’s there?). The brand-spanking-new Olympic Park loop line opened in 1998, with most of the Homebush Salesyard Loop repurposed to be a part of it.

Now, since that was a little…dry, let’s get wet.

The Sydney Olympic Park Aquatic Centre was the first part of Olympic Park to be constructed following the closure of the abattoir, unless you count Bicentennial Park, which opened in 1988. The Aquatic Centre opened in 1994, with the rest of the park completed by 1996. As such, the Aquatic Centre is the ‘middle child’ of the Olympic Park, with a design sensibility halfway between Bicentennial Park and the stadiums that followed. It’s a strange beast, and one made even stranger by my near-absolute certainty that when it first opened, its entrance was in fact this:

Sometime in 1995, I attended a birthday party at the exciting new Aquatic Centre, which was rumoured on the playground to have a whirlpool and slides. I don’t remember any slides, but I do have a distinct memory of our posse leaving behind a rubber WWF wrestler toy, tossed high up in those bushes on the left in a fit of excitement…while we were hanging around the entrance. Does the Iron Sheik still reside in those bushes today, subsisting on a diet of ants, rainwater and the occasional small bird? Nearly 20 years later, I still wasn’t game enough to climb up and find out. But I did go in for a closer look…

Sometime in 1995, I attended a birthday party at the exciting new Aquatic Centre, which was rumoured on the playground to have a whirlpool and slides. I don’t remember any slides, but I do have a distinct memory of our posse leaving behind a rubber WWF wrestler toy, tossed high up in those bushes on the left in a fit of excitement…while we were hanging around the entrance. Does the Iron Sheik still reside in those bushes today, subsisting on a diet of ants, rainwater and the occasional small bird? Nearly 20 years later, I still wasn’t game enough to climb up and find out. But I did go in for a closer look…

The appearance of those bolt marks, where the original entry sign was probably attached, seems to validate my memory of this being the main entrance. The doors underneath now serve as an emergency exit. If anyone can shed some light on this mystery, drop a line in the comments below. My theory is that when the Aquatic Centre opened, the entrance was here because it faced away from the abattoir site (and at the time, a huge construction site), but when the rest of the park was completed, the entrance was moved around to the opposite end of the facility, a spot which pretty much faces the Abattoir Heritage Precinct (and everything else, in keeping with the Olympic spirit of inclusion and togetherness). Today’s entrance looks a lot more ‘Olympic’ anyway, so it was probably a change for the best. Still…

Our last stop is just down the road from the Aquatic Centre. Back in the 70s and 80s, Swire (then Woodmasons Cold Storage) would have been one of the places to store the freshly processed animal carcasses on ice before being shipped to the nearby butcheries and markets. For a cold storage facility (and for Dairy Farmers), this was the perfect location…when the abattoir was there. How it’s still able to do business is a stone cold mystery, but I guess that’s why they’re no longer Woodmasons.

Our last stop is just down the road from the Aquatic Centre. Back in the 70s and 80s, Swire (then Woodmasons Cold Storage) would have been one of the places to store the freshly processed animal carcasses on ice before being shipped to the nearby butcheries and markets. For a cold storage facility (and for Dairy Farmers), this was the perfect location…when the abattoir was there. How it’s still able to do business is a stone cold mystery, but I guess that’s why they’re no longer Woodmasons.

See you next time, when we’ll attempt to go for a drive…

F4 Expressway/SWR Western Motorway/M4 Freeway – Concord, NSW

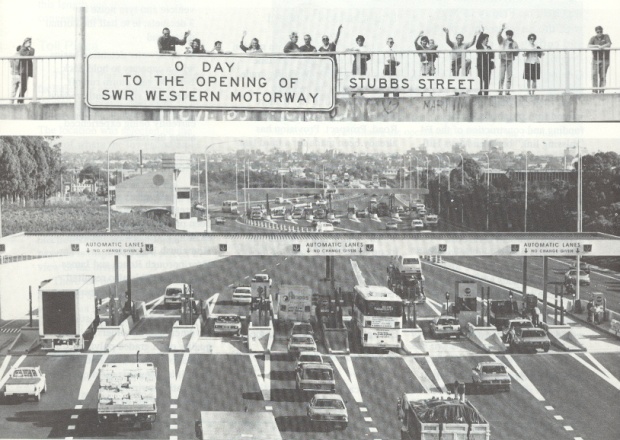

As promised, we’re now going to plunge into the half-assed history of the M4 freeway’s eastern terminus. I’m imagining you’re already as joyful and excited as those people on the bridge above, but don’t peak early – we’ll dig up some good stuff. If I do a half-assed job, consider it an homage.

After World War II it became clear that Parramatta Road wasn’t going to cut it anymore as a way of getting people to and from the western suburbs of Sydney, which had exploded in terms of population. Of course, in those days, Leichhardt was a western suburb, but you get the idea. In 1947, the newly created County of Cumberland Planning Scheme identified a possible route for an expressway which would connect Glebe to the Great Western Highway at Lapstone (of the treacherous Lapstone Incline fame). In reliably speedy NSW Government fashion, the corridor of land was reserved in 1951.

As an aside, I’d just like to shine the spotlight on my ignorance: I had no idea what Cumberland County was, and I was surprised to learn that not only was it created by Governor Arthur Phillip in 1789 and encompasses most of the Sydney metro area, but that there are 141 counties in New South Wales. A shadowy cabal of local government councillors would elect the Cumberland County Council, which then had a powerful influence over town planning in metro Sydney. Spooky stuff.

Anyway, the M4’s construction started backwards, with the first stage completed at Emu Plains in the late 60s. The late 60s. After the plan was formed in 1947. Yeah.

As the freeway crept closer and closer to Sydney, the pocket of land set aside to relieve the ever-building traffic pressure in the city waited patiently for its turn.

It’s still waiting.

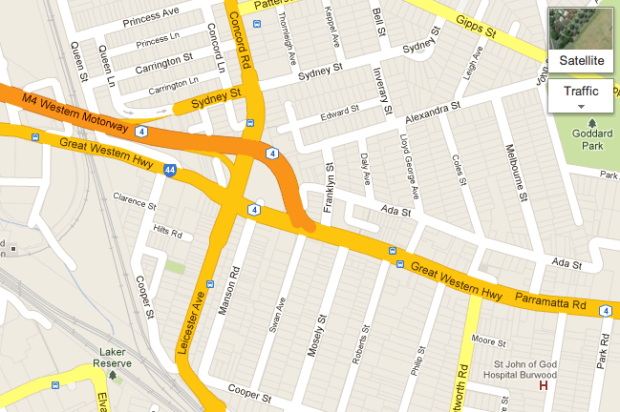

This is the start and end of the M4, and as close as the freeway gets to the city. Every day, traffic from the western suburbs and beyond is ripped from the (theoretically) 90km+ flow into the waiting 60km arms of Parramatta Road, Concord. Citybound motorists must then contend with the stop/start rhythm of Sydney’s oldest road and a new nightmare: traffic lights. If this sounds awkward, it’s because it is. And it looks even more awkward:

In 1976, the F4 freeway (as it was then known) was all set to drill right through the inner west and end up at its intended starting point in the city, Glebe. But Glebians (?) had had over 20 years to prepare their outrage and protests, so the Department of Main Roads found itself staring down a pissed off neighbourhood that feared the freeway would shatter its layout and atmosphere. In what would be the first of many such moves for the NSW Government, it backed down. The Concord to Glebe section of the freeway was abandoned, and a backup plan was hastily slapped together.

Also hastily slapped together were the physical components of the eventual fix, which was to spill the M4 onto Parramatta Road and hope that it all worked fine. In 1982, more than 30 years after planning had commenced, the section of the M4 between Concord and Auburn was opened to traffic, despite the next section between Auburn and Granville not being complete.

What a shemozzle! Although the rest of the freeway west of Concord was eventually completed (pretty much), it’s the section between Concord and Auburn that remains the most interesting and telling of the struggles that went into constructing it. With the O’Farrell Government now gearing up to deliver on its promise to complete the M4 (via a tunnel system, natch), it’s as good a time as any to see what kind of stopgap measures we can look forward to.

Where the M4 itself joins Parramatta Road, it LITERALLY joins Parramatta Road in a series of glued on slabs of cement. It’s easy to see the difference in road material here..

…here…

…and here. This is because the entrance to the M4 as it is today was originally part of Concord Road, which was relocated a block to the west. Why? Bear with me…

When this section was completed in 1982, the one-way Sydney Street was the only way off the M4. Traffic would then spill into Concord Road, which at the time followed a different alignment…

…being this, the current end of the M4. To accommodate more traffic, Concord Road was realigned to cross Parramatta Road instead of joining it.

Concord Road was extended towards Leicester Street on the other side of Parramatta Road, and the former curve was filled in by parkland and a bus stop:

So if you’ve ever wondered what this big bit of nothing was all about, that’s the story, although it could be argued that providing more access for buses adds to Parramatta Road’s problems, but that’s another story.

A tunnel was dug here between the M4 and Concord Road to form the overpass that exists there today, and to direct the traffic flow onto Parramatta Road. What was the fruit of all of this effort? One set of traffic lights is bypassed by eastbound traffic.

This restructure meant that Young Street, which in 1982 acted as the eastmost on-ramp for the M4, was cut in half by the new end of Concord Road. What was once one of the most important streets in Sydney now ends with a whimper:

…where once it would have joined the M4 it now provides access to a unit block’s carpark.

As mentioned, the other problem the M4 faced in 1982 was that it stopped at Silverwater. You could get on at Young Street, belt down the freeway at 90km/h in your Holden Monaro for about five minutes before being dumped back onto Parramatta Road, the defacto western expressway, at our old friend Melton Street.

Yes, this is the sight you would have faced exiting the M4 between 1982 and 1984, when the next segment was completed. You would have zoomed up past the school and the Melton Hotel, and then back onto Parramatta Road for the next million years if you were trying to get to Springwood. If we look a bit closer, we can see where the exit ramp used to be:

In the bushes between Adderley Street and the M4 you can see a clear path the motorists would have taken to rejoin Sydney traffic. I’m assuming the RTA has set this land aside for future widening of the freeway, as if that will ever happen, but in the meantime it gives us that vital link to the past. Once again, a seemingly insignificant little road like Melton Street actually did have a grander place in the scheme of things. Parramatta Road: where anything can happen.

Further up from Melton Street is the Silverwater mainstay Stubbs Street, as seen in the very first picture in this article. The M4 proceeds under the Stubbs Street overpass…

…which was completed in 1981 to mark the end of this section of the freeway.

Once the next section between here and Granville was completed in 1984, Melton Street was once again exclusive to pub patrons and parents dropping off their kids, while motorists were free to drive on to the west.

Or were they?

By 1989 only a small section of the M4 as we know it today was missing, and a private consortium, StateWideRoads, was contracted by an exhausted NSW Government to finish the job. As we all know, a grand don’t come for free, so by the time this missing link (and some hastily approved widening) was completed in 1992, someone had to pay.

That someone was you.

It was determined that the section between James Ruse Drive at Granville and Stubbs Street, Silverwater was the section through which the majority of cars would pass, thus ensuring the shortest possible time for a toll to be in place. In May 1992, $1.50 was required to continue out to the western suburbs. By the time the toll was removed in February 2010, over $970 million had been paid to pass these booths.

Today, there’s little apart from the alignment of the lanes to suggest that the toll booths were ever there, but other remnants of the M4 project have left a more lasting mark all over Sydney. The freeway is back in the hands of the NSW Government, which is akin to returning an abused child to their abusive parent. As the battle to complete the M4’s route into the city rages on in state parliament, Federal Opposition Leader Tony Abbott has even expressed support for the completion should he win government at the next election. Thousands of motorists a day are still inconvenienced by the half-finished freeway. One accident on the M4 causes traffic chaos all over the city. The Eastern Suburbs are still effectively isolated from the rest of Sydney due to a lack of motorways….so I guess there are always upsides. There’s been talk of reinstating the toll to pay for what would by now be a very expensive couple of kilometres. In 1977, the projected cost of completing the M4 from Concord to Glebe as intended would have been $287m.

The M4 is only 46km long.

Maybe if it ever gets finished, it’ll be linked up to the Western Distributor so that it can actually start distributing people to the west instead of, you know, nowhere.

TRAFFIC STOPPING UPDATE: Thanks to Burwood Library’s archive of interesting old stuff, you can now enjoy this old pamphlet detailing the opening of TWO new segments of the F4 back in 1982. Even better is that this article’s diagrams illustrate the progress of the F4 almost as well as the above article. You all thought I was mad when I wrote this one, but who’s mad now?

Vend-A-Card/Pez Dispenser – Strathfield, NSW

This one’s a bit different to the usual stuff, but if you’re my age and demographic (and I’ll bet you’re not) this’ll appeal to a long-forgotten part of your brain. Prepare your past life for a future shock.

When I was a kid, if a big budget movie was coming out to appeal to all six of my senses (you know you have more when you’re a kid), chances are one of its avenues of assault would be a series of trading cards. On me, it worked like a charm. I had a tonne of them, and they made sure that each set was an OCD’s delight. You had to order them correctly in the official collector albums, you had to get all the inserts, you could even collect the wrapper variants. Nothing was more boastworthy at school than the rarest inserts or a complete set, but completing a set wasn’t as easy as you’d think. Trade negotiations between jealous and selfish five-year-olds were more heated than that era’s US-Soviet peace talks, and eventually you’d reach the point where you only needed one or two cards to be done with the whole business. A pack would typically contain seven cards or more. How to solve this dilemma? That’s where Vend-A-Card came into the picture. A vending machine for cards. The only thing better for a kid my age would have been a vending machine for action figure accessories you’d managed to lose. The machines would typically play host to single cards (at inflated prices), and sometimes packs as well, presumably because newsagents had gotten sick of snotty kids coming in and chewing them out for picking the wrong pack off the shelf (if I’d wanted Spiderman 94s, I wouldn’t have asked for Spiderman 95s, would I?). It should say something about the popularity of trading cards at the time that these beasts could even exist. Many a set was completed through the luck of spotting that last elusive #33 staring out at you through the Vend-A-Card, and for a time they were heroes.

That’s where Vend-A-Card came into the picture. A vending machine for cards. The only thing better for a kid my age would have been a vending machine for action figure accessories you’d managed to lose. The machines would typically play host to single cards (at inflated prices), and sometimes packs as well, presumably because newsagents had gotten sick of snotty kids coming in and chewing them out for picking the wrong pack off the shelf (if I’d wanted Spiderman 94s, I wouldn’t have asked for Spiderman 95s, would I?). It should say something about the popularity of trading cards at the time that these beasts could even exist. Many a set was completed through the luck of spotting that last elusive #33 staring out at you through the Vend-A-Card, and for a time they were heroes.

Then 1997 happened. Topps and Skybox execs were jumping from the 40th floor windows of their buildings and hitting the streets below among scores of pedestrians too busy playing with their Tamagotchis to notice. The videogame industry had inflicted a Dim Mak upon trading cards, and things would never be the same. The Vend-A-Card machines were destined to become landfill, and they, once my eternal saviours, exited my consciousness…until about two weeks ago.

Strathfield bowling alley’s arcade isn’t huge, and certainly isn’t huge enough to contain THREE Vend-A-Card machines, but they made it happen. Even back in the day you wouldn’t have seen a Vend-A-Card at a bowling alley despite their ubiquitousness, but Strathfield quietly installed these three to provide for the needs of the masses once more. But, I hear you say, cards are an anachronism. Surely they wouldn’t be vending cards these days.

You’d be right.

The sight of a relic from 1995 reborn as a dispenser dispenser made me extremely thankful for the Nurofen.

The sight of a relic from 1995 reborn as a dispenser dispenser made me extremely thankful for the Nurofen.

OK Restaurant/Master Kwon’s Pro Tae Kwon Do Academy – Enfield, NSW

The owners of Enfield’s OK Chinese Restaurant mustn’t have had much self confidence. C’mon guys, you could wine and dine there…surely it was better than just OK?

In a place like Enfield, where the competition ranges from good to great, being merely okay didn’t help the restaurant stay afloat. These days, all that remain are the neon signs which, in years gone by, would unintentionally act as the OK’s own private lighthouse, warning off hungry passers-by with the promise of an average eating experience.

There’s a silver lining, however: the businesses occupying OK’s space today have all learned the most important lesson of the OK saga. We have Mr. Viscontini Fine Italian Food, Master Kwon’s Pro Tae Kwon Do Academy and Big Clean cleaning supplies, all of which sound unusually empowered and boastful. If not for the OK’s sacrifice, we might today be looking at Viscontini Not Bad Italian Food, Master Kwon’s Intermediate Tae Kwon Do Academy and the Moderate Clean Supplies outlet.