NSW State Brickworks/Brickpit Ring Walk – Homebush, NSW

In a time when building a house meant plenty of brick, mortar and asbestos as opposed to 100% pure cladding, a housing boom meant it was time to get digging. The State Brickworks at Homebush was established by the NSW Government in 1911 to (publicly) provide for the demand for public housing and (privately) to shatter the stranglehold private owners had on the brickmaking industry, because no one makes money without the NSW Government getting a piece of the action. This greedy plan backfired at the onset of the Great Depression, when demand plummeted and the site started operating at a major loss. Ironically, it was sold to a private firm in 1936, and closed soon after.

Of course, the history of bricks in Sydney reaches back much further than Homebush. Brickfield Hill (near Haymarket) owes its name to its brickmaking past, and the St Peters brickyards are still in plain view – I just haven’t been there yet. The Homebush site was adjacent to the State Abattoirs, presumably to maintain the ambience, but more likely because the ground was rich in necessary brick ingredients. The Homebush Brickworks had also served to replace the troublesome State-run sand lime brickmaking operation at Botany, which had in 1914 fallen victim to a labourer strike, and never recovered.

After World War II, during which the site had been used as an ammunitions depot by the Navy, the NSW Government sensed an opportunity to make money, and reopened the Brickpit just in time for the second housing boom. If the first boom was a Newcastle, this one was somewhere between a San Francisco and an Indonesia. Chances are that at some point during your life in Sydney, you’ve stayed in a house built with bricks from Homebush. The site even had its own train station for workers to use, which opened in 1939.

It should be mentioned that during the 60s, 70s and 80s, the Brickworks was known by a different name to young hoons and petrolheads looking to blow off some steam on a Friday or Saturday night. ‘Brickies’ was a hot destination for drag racers setting off from the Big Chiefs (Beefy’s) burger joint on Parramatta Road, tearing off up Underwood Road in their Monaros towards Brickies Hill. This circuit can be seen in the 1977 film FJ Holden, which will be a major part of this blog sooner than later. The onset of development put a stop to this, but a subtle, if bizarre, homage to that era has been paid through the naming of certain streets around Hill Road, once the drag strip finish line: Nuvolari Place, named for Italian racing legend Tazio Nuvolari, and Monza Drive, after the endurance race of the same name. Sydney also hosted its first V8 Supercar event at the Olympic Park in 2009, echoing the days of weekend supercar stardom in less developed decades. Residents could still nostalgically enjoy extreme noise pollution and rowdy behaviour, but at least this time it was corporately sponsored.

From an industrial standpoint, they might as well have been making gold bricks at the ‘works for the next three decades…and then the 80s happened. The boom died down, the money dried up, and the Brickworks, which had for the most part of the 20th century poisoned the surrounding land and Homebush Bay, was clumped in the same basket as the increasingly irrelevant State Abattoirs and the volatile Rhodes industrial area – it had to go, but before it did, the crew of Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (or perhaps The Conqueror 2, just give it a few years) chose the toxic site as a filming location. In 1988, the Brickworks were closed for good. Like the rest of the State-owned Homebush industrial zone, it was included in plans to reshape the area into the Sydney Olympic Stadium in 1992. The Brickpit was to become the tennis centre.

And so it would have gone, had not a funny, completely unexpected thing happened. The green and golden bell frog was nearing extinction by 1992. Once abundant in Sydney, numbers had fallen so low that a special breeding program was established at Taronga Zoo in the hope that the frog could be saved. As preliminary work was being done, 300 of the small frogs were discovered living in the quarry. Several times since, colonies of the undeniably appealing frog have turned up at proposed development sites, halting work, ruining plans, and causing PR-illiterate development bigwigs to shit a…well, you know. The frogs are no longer critically endangered, but they still have a long way to go.

As the rest of industrial Homebush was transformed for the Olympics, the Brickpit itself followed suit, undergoing heavy remediation. It’s now an environmental feature of the Olympic Park, and features the wonderful Ring Walk, a walkway suspended above the former Brickworks site complete with a giant pond filled with what can only be described as Smylex. Those frogs must be mighty happy.

It’s funny…we spent the better part of last century digging this place up and sending it off all over the city for our homes, but the frogs cut out the red tape and came to the place itself, making it their home in less than a decade. We didn’t start building units here until years later. Am I saying a frog could run Mirvac or Lend Lease?

Ribbit.

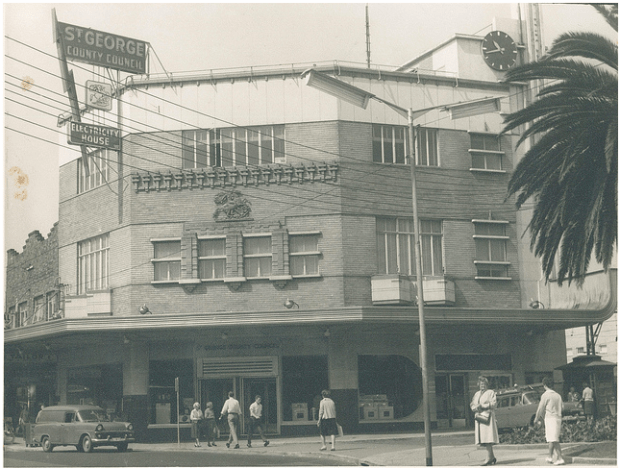

Electricity House/Bank of China – Hurstville, NSW

The St. George County Council was established in 1920 to control the distribution of electricity within the Municipalities of Bexley, Hurstville, Kogarah and Rockdale, and was the first of its kind in Australia. In 1939, this building was constructed for the St. George County Council, presumably as a way of showing off just how fancy and powerful the Council was. During the early years of the SGCC, it was reported that St. George residents enjoyed the cheapest electricity in the country.

By 1963 it appears that most of the county’s electricity was being distributed right to this building, what with all the neon signs. Absolute power corrupts, so to speak. The St. George County Council enjoyed its name up in lights until 1980, when it was amalgamated with the Sydney City Council, itself rebranded in 1991 as Sydney Electricity and in 1996, EnergyAustralia. Now, St. George residents pay too much for electricity just like the rest of us.

Today the building has become a branch of the Bank of China, among other things, and doubtless many electricity bills are paid here. They’ve still got the neon happening there in the bottom right, perhaps just to prove that they can. It’s for a dental clinic, not a place you often associate with neon signage. The clock is a poor facsimile of its predecessors, too; also, it doesn’t work.

It’s gotta be a kick in the tablets when you can only get the ex-Minister for Works & Local Government to unveil your building. Spooner, a Conservative, had resigned as Minister a few months earlier after publicly describing that year’s State Budget as ‘faked’. He was also responsible for regulating the appropriate cut of mens bathing suits, insisting on the full-length one-piece. Sort of like the Tony Abbott of his day, in that way.

Shea’s Creek/Alexandra Canal – Mascot, St Peters, Alexandria NSW

You’re looking at Sydney’s most polluted waterway. And I thought Rhodes was bad.

In the late 1880s (it’s always the 80s), someone envisaged a grand canal stretching from Botany Bay to Sydney Harbour. It would start at the Botany Bay end of the Cooks River, and lead all the way through the city before opening up at Circular Quay, thereby giving the Eastern Suburbs the island refuge from the great unwashed they’ve always wanted. To that end, I’m surprised it never happened.

Shea’s Creek, a small offshoot of the Cooks River, was chosen as ground zero for the new tributary, which was supposed to act as an access route for barges to transport goods between the multitude of factories set up along the creek in the area. Factories including brickworks, tanneries and foundries. Factories that drained their runoff directly into the canal. A canal that is, according to the EPA, “the most severely contaminated canal in the southern hemisphere”. So keen to pollute were the industrial warlords of yesteryear that they had to invent waterways to defile.

At the time the canal was constructed, Sydney’s roads were a terrible mess completely unsuitable for transporting goods, making an aquatic access route more practical. Thankfully, Sydney’s roads today…uh…they…they’re pretty uh…let’s get more canals happening.

Between 1887 and 1900, Shea’s Creek was ripped up and turned into the canal. By 1895 it was looking unlikely that it would ever reach Sydney Harbour. The NSW Government had decided that as a sewer, the Shea’s Creek Canal as it was known then was doing a good enough job as a carrier of stormwater and runoff, and that there probably wouldn’t be a need to spend all those pounds carrying on with the project. Tenders were called again to complete the canal in 1905, but there were no takers.

The canal was renamed the Alexandra Canal in 1902, after the then-Queen Consort Alexandra. Coincidentally, the suburb that the canal ended in, Alexandria, was also named for her. I bet she was proud, too.

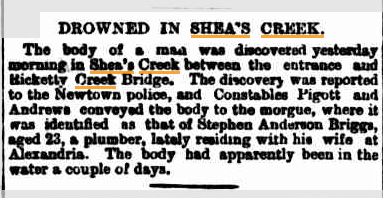

This is how it ends. The mighty canal winds down to a stormwater drain, which then continues to wind up through Alexandria before disappearing. Apparently, the cost of the already 4km canal was so prohibitive as to cancel the rest of the project. It might also have been that the powers that be were trying to save lives, for in creating the Alexandra Canal, they had also created…a bloodthirsty monster!

There have been several attempts since 1998 to clean up the canal, add cycleways (more cycleways!), cafes and restaurants, and generally make it a nice place to be.

As you can see, it hasn’t happened yet. Maybe when the city’s insane lust for cycleways finally stretches the canal to Sydney Harbour, that fantasy can be realised.

Western Distributor On-Ramp/Road Hammock – Sydney, NSW

Here’s something completely stupid: this carriageway is the Western Distributor passing over Kent, Day and Margaret Streets near Wynyard. Below it is…a bit of road that…goes nowhere, and does nothing.

The Western Distributor began life in the early 1960s as a way to relieve traffic on the Harbour Bridge. Sydney’s extensive underground rail system meant that the Distributor couldn’t be built as a series of tunnels, so viaducts were the sensible alternative. That’s where the sense stopped.

The only reason the Western Distributor existed was because the designers of the Harbour Bridge and existing road system didn’t use enough foresight. You’d think that planners of the WD would employ twice as much foresight to make sure that further modifications weren’t necessary. Well, two times nothing is still nothing.

The original plan for the Western Distributor had westbound traffic exiting the city via the Glebe Island Bridge. For those who aren’t familiar with the bridge in question, here’s a picture:

That’s it there, below that huge, multi-lane bridge. If you can’t see it, squint. The two-lane Glebe Island Bridge had been built in 1903 to provide access to the Glebe Abattoir, and it includes a swing bridge to allow boats through. Surprisingly, this bridge proved to be unable to handle the traffic spewing forth from the Western Distributor, and in 1984 the NSW Government proposed another bridge. Good thinking! The Anzac Bridge was completed by 1995 (!), and opened in December of that year. It features a great height to allow boats through.

Of course, when the Distributor had been designed, it was flowing towards a small bridge. Now that it had a giant, capable bridge to lead into, the one-lane road itself suddenly seemed a bit lacklustre. In 2002 (!!), work commenced to widen the Western Distributor throughout the city, which brings us back to our original ridiculousness.

This bit of suspended road was originally an on-ramp for the Western Distributor, with access from Margaret Street. When the road above our piece here was widened, it claimed the on-ramp’s space and ended Margaret Street’s usefulness in the scheme of things. For a time it was used as a parking bay (illustrating the lengths the City of Sydney Council is willing to go to to make a buck out of parking). The ramp was then severed at both ends, and now sits hanging above the street, useless and surreal.

The happy ending to this story is that after the implementation of each of these emergency patches to the highways of Sydney, traffic in the city was never a problem ever again.

Broadway Theatre/Jonathan’s Disco/Phoenician Club/Breadtop – Ultimo, NSW

These days, this building on the corner of Mountain Street and Broadway, Ultimo, houses a convenience store, apartments, and our old friend Breadtop, but the inconspicuous facade hides a colourful and tempestuous history.

Built in 1911, the building started life as the Broadway Theatre, a cinema. With the advent of TV, this was one of many suburban cinemas that had fallen by the wayside by 1960, when it closed. In 1968, it was acquired by nightclub owner John Spooner and converted into Jonathan’s Disco, where it became well known as one of Sydney’s prime live music venues. Sherbet and Fraternity both got their big break at Jonathan’s, playing residencies involving six hour days for months on end. Imagine the poor disco staff having to listen to six hours of Sherbet a day for months. Perks of the job…

In May 1972, Jonathan’s Disco was gutted by fire. I can’t help but think it was one of those beleaguered staff members. “HowZAT?” they’d’ve quipped as they flicked their cigarette into the freshly-poured puddle of gasoline. The damage was extensive, and required a complete internal refit before it was opened again in 1976 as a ballroom dancing studio.

The Sydney City Council granted the Maltese community use of the premises as a licensed venue in 1980, when it became the Phoenician Club. Once more, the site became one of Sydney’s most popular live music venues with local bands such as Powderfinger and Ratcat playing gigs there throughout the late 80s and early 90s. Nirvana played their first Sydney show there in 1992 – a far cry from Sherbet. Around this time, the rave scene exploded in Sydney; a development that would lead to the end of the Phoenician Club.

Anna Wood, a 15yo schoolgirl from Belrose, attended an ‘Apache’ dance party at the Phoenician in October 1995, where she took ecstasy. Her resulting death shocked Sydney and enraged then-NSW Premier Bob Carr, who declared war on the Club. A series of fines and restrictions imposed on live venues in the wake of Wood’s death led to the closure of the Club in 1998 and the decline of Sydney’s live music scene which continues today. Good thing Wood wasn’t killed by a pokie machine.

From 1998 the site sat derelict, just in time for the Olympics. Nothing international visitors like seeing more than abandoned, graffiti-tagged buildings. In 2001 it was completely redeveloped internally, and today satisfies Carr’s idea of a venue put to good use.