Bank of New South Wales/Westpac/Embassy Conference Centre – Chippendale, NSW

Oh, that’s nice.

But what’s this? Couldn’t make it through century two, then?

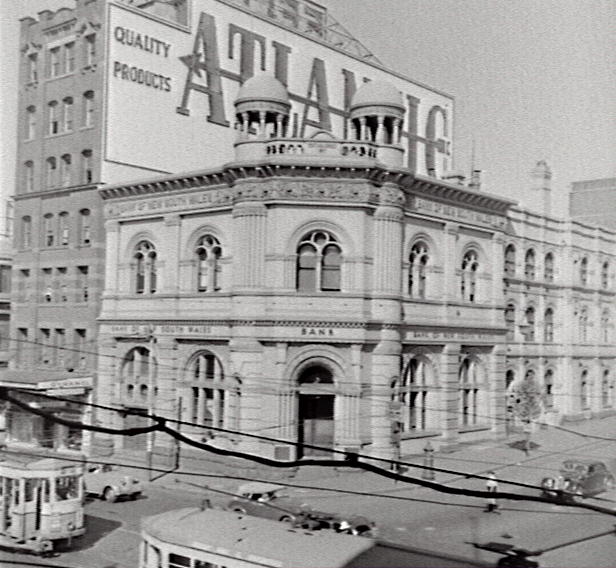

Actually, the Bank of NSW (later Westpac) held on here for a good 30 or so years past 1960. Let’s take a look:

As we’ve previously been over, the Bank of NSW has a long and illustrious hiszzz…huh, wha? Oh, do excuse me. The revered financial institution was established in 1817 without a safe. Yes, you read that right:

In the spirit of that ridiculousness, tomorrow I’ll be establishing an amusement park: Fast Rides of the Near Future. Anyone got any rides I can borrow? Free entry for a year if you do!

In 1860, the BoNSW started to branch out – literally. The bank’s first branch was established here on Broadway that year. But what flies in the ’60s sinks in the ’90s, and by 1894 changes had to be made. The powers that be summoned Varney Parkes (son of Sir Henry and former Bank of NSW employee) to design the current building (complete with it’s own gold smelting facility), unceremoniously treating their number one son like number two in the process. In fact (as we’ll see), that plaque at the top of the page is about as sentimental as Westpac cares to get (but remember, you’re not just a number 🙂 ).

Actually, maybe in 1955 you were. Oh, check it out: the postbox by the corner is still there!

1982 saw the Bank of NSW merge with the Commercial Bank of Australia to form Westpac, presumably to confuse customers. You can guarantee they would have netted some poor old biddy’s cash in the changeover. To aid the public through this confusing time, all branches were poorly rebranded with the Westpac name, and the Railway Square spot was no different.

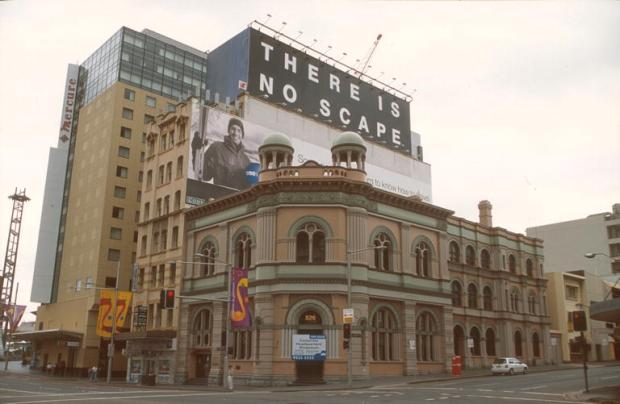

Here it is in 1992, in glorious colour for the first time. In that same year, Westpac suffered a $1.6b loss, a record for any Australian corporation at the time. Staff were let go en masse, and that would had to have affected this branch. Luckily, anyone forced out the door would have seen the old Sydney City Mission logo behind them there. I wonder whatever happened to that? Someone should get on that.

Despite Westpac’s extensive refurbishment of the building in 1989-90, the bank was hit too hard by ’92’s recession. By 2000, the building that had once been the bank’s pride and joy was just another ‘For Lease’ along George Street, just in time for the Olympics.

Today, the bank’s purpose is to serve as a function centre. Why one would be needed right beside the Mercure, which presumably has its own, boggles the mind…unless. UNLESS…when the Mercure set themselves up, they put an ad in the paper advertising for the lend of a conference room…

Pizza Hut/Moo-ers Steakhouse/For Lease – Long Jetty, NSW

When someone or something beloved is replaced, it’s not unusual for the usurper to find itself under fire, the subject of blistering scorn (and never moreso than right here on this blog). In the case of Moo-ers, a steakhouse up near The Entrance, it seemed like they picked the wrong shoes to fill.

In 2008, Moo-ers maa-nagement became concerned about the quality of meat they were receiving; hogget and mutton were being misrepresented as lamb, yearling as veal. The definition of beef cuts was being stretched by local suppliers; a shipment claiming to include sirloin, porterhouse and striploin cuts would be found to contain nothing but the one generic cut of beef. I wonder if this was happening with their seafood as well: shrimp instead of prawns, carp instead of everything else.

Moo-ers raised the issue with the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Committee (SRARAATC *ahem* excuse me), hoping for tighter naming guidelines for meat. With most of their menu being meat, any substitution or downgrade in quality was hurting the Moo-ers brand.

Was anything ever done? Was the integrity of the Moo-ers menu salvaged? To answer those questions, cast your eyes upwards to the picture. Notice anything…for lease? My expert guess is that Moo-ers’ shipments of generic meat was in keeping with what the previous tenants had received. I mean seriously, if you can tell me what kind of “meat” the Pizza Hut “ground beef” is meant to be, then congratulations – there may be a spot for you on the SRARAATC.

Toyworld/Chuan’s Kitchen – Hurstville, NSW

When I turned four, I was taken for a walk up the street to the local toy shop and allowed to choose a present. The shop was a Toyworld – you remember, one of those big, purple deals with the giant purple bear wearing a cap in the modern fashion.

As a brand, Toyworld’s history dates back to 1976, when parent company Associated Retailers Limited realised that name wouldn’t look as good in rainbow colours on a toyshop marquee. Toyworld was launched as the retail group’s toy arm at a time when toys themselves were about to be ripped from their ancient comfort zones and thrust into a golden age of action figures by the blockbuster success of Star Wars. Riding this phenomenon from the late 70s through the mid 80s on brands such as Star Wars, Masters of the Universe and Transformers, Toyworld changed the face of toy retailers in Australasia, emblazoning that happy purple bear on hobby, sport and toy shops everywhere. Toyworld itself isn’t too sure about its own legacy, as the embarrassingly evident indecisiveness on its website demonstrates.

A man and his ride, 1981. Image courtesy whiteirisbmx/OzBMX.com.au

They didn’t entirely abandon their sporting goods heritage, either. Plenty of kids would have unwrapped a BMX (can you wrap a BMX? wouldn’t that look awkward as hell?) in front of jealous friends on birthdays or jealous siblings at Xmas, completely unaware that a purple bear had profited from their joy. For me, the sporting goods section of Toyworld was the absolute no-go zone. Who cared about some cricket pads when there were NINJA TURTLES over here? Or what about down there, in that bargain bucket out the front, for five bucks each?

On that glorious February day, I chose as my present the three Ghostbusters I was missing (I already had Venkman). My logic: I was turning four, and now I would have four of them. It worked – before long, the Ghostbusters were a team once more, zapping those crazy rubber ghosts until I saw an ad for Batman figures on TV and coloured Venkman black (see pic) in the hope he’d suffice. He didn’t.

And so my direct association with Alf Broome’s Toyworld ended, but I never forgot it. It was a hard place to forget purely on a visual level; from the purple frontage to the bear to the giant LEGO logo plastered on a mysterious door beside the shop, the whole place was designed to be an assault on a child’s senses, and oh what a glorious assault it was.

But what I didn’t know – couldn’t have known – at the time was the turmoil within. By 1988, Hurstville Toyworld was under siege, with struggles on local, national and even global fronts. Behind that happy purple face was a saga of bitterness and commercial impotence in the face a formidable threat to the entire toy industry.

As the article says, Broome’s toy shop had been around since 1971, first as the sports and toy shop, and then as Toyworld. Broome says that business boomed until 1986, when local opposition (likely the nearby Westfield, which had been constructed in 1978) made inroads into his business. The immediate effect of this encroachment was evident in the bargain bins outside – $5 Ghostbuster figures is a sign of the times.

Then, as Broome puts it, a “ripper recession” devastated any chance of recovery in 1990, with severe storm damage that same year not helping matters. Another strange point of impact upon sales mentioned by Broome was construction of a ‘new plaza’ by local council. Hmm…I’ll have to look into that one.

Broome banked it all on a healthy Christmas ’90 trading period that never came. The recently refurbished Westfield offered stiff competition, and globally, toys had begun their decline in popularity with the rise of video games. Even with the 1988 advent of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, nothing could be done to stop the Nintendo/Sega tag-team, which by 1992 had all but ended the age of dedicated toy shops, relegating Barbies and He-Men to toy departments, or bigger chains like World 4 Kids. Rather than face the likelihood bankruptcy, Alf Broome chose to walk away.

That was 1991.

Today, the building still stands, despite the near constant construction and refurbishment of the area. Of course, it’s been standing there since 1899, and has probably seen more failure than you or I could ever imagine. The first post-Toyworld occupant was Belmontes Pizza Shop, and man was I ever bitter. I couldn’t believe the toy shop had gone, and pledged never to frequent the usurpers.

Chuan’s Kitchen, the current successor to a line of failed take-aways that has populated the site since Belmonte hit the bricks, was not open today even if I had wanted to spend cash there. The take-away might have enraged me, but what outright scandalised me as a child was that the mysterious door once adorned with that bright, colourful LEGO insignia had been replaced by an adult shop – as far from a kids toy shop as was commercially possible. Originally L.B. Williams’ Adult Book Exchange, today it’s the far more generic Hurstville Adult Shop.

Toyworld limps on, mostly in country locations. I swear, every country town I’ve ever visited has had a Toyworld. Why? And while I’m asking unanswerable questions: what was behind the door back when it had the LEGO sign on it? What did Alf Broome do next? Just who was L.B. Williams? Perhaps we’ll never know. But Alf, if you’ve Googled yourself and have ended up here, I want you to know something. Back in 1991 you may have been “the man in the wrong place, at the wrong time, in the wrong business”, but in 1989, when I went in and was gifted those Ghostbusters, your shop was the world to me. And this is just my story – imagine the number of kids who would have left that purple shop happier than they’d ever been. Heck, reader, it might have been YOU. That kind of thing might not have been able to pay rent, staff wages or stock prices, but it does guarantee your immortality, Alf. You’re welcome.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL UPDATE:

It’s cool when things like this happen. As you’ve read above, I presented my case on the flimsiest bit of evidence, but Your Honour, I now present to the court…EXHIBIT B.

When the building behind it was demolished, it allowed for a prime view of the back of Chuan’s Kitchen. Why should this matter? Let’s take a closer look…

Oh, what’s that? I can’t quite make it out…CLOSER STILL!

Boom. There it is. Today. You could go and see it right now. At some point in the Toyworld saga, they thought to put up this logo on the reverse side of their building. Why?

Perhaps at the time the Liquor Legends building wasn’t there, providing uninterrupted views of the beaming purple signage. Maybe the signwriters were doing a two-for-one deal and the owner was going to get his money’s worth, damn dammit. Or maybe the truth is far more sinister… Either way, it took the demolition of the bottle shop (all in the name of progress) to unearth this treasure. Within each seed, there is the promise of a flower. And within each death, no matter how big or small, there is always a new life. A new beginning.

Della Cane/Boomalli & Recollections – Leichhardt, NSW

These days, Leichhardt is home to Recollections, a country-style furniture warehouse, and one door up is Boomalli, an Aboriginal artist cooperative. In this instance, Recollections have wisely chosen to drop their full business name so as not to create a microcosm of colonial Australia right here on Flood Street.

But the earliest settler at this warehouse lives on through this tiny little detail. It’s old, it’s worn, it’s even got a bit snapped off…but it’s still just strange enough to make an observant passer-by take pause. Leichhardt’s hardly a tropical paradise. What’s the story?

The answer lies back in 1991, and this ad for Della Cane. No building that ugly could exist twice, and the interior looks like Fantastic Furniture met Jurassic Park.