Cumberland Hotel/TK Plaza – Bankstown, NSW

There isn’t much call for an old English-style hotel pub in Bankstown these days. This particular part of the city, Old Town Plaza, is especially bereft of watering holes thanks to the enormous Bankstown Sports Club around the corner.

Yes, there’s the Bankstown Hotel and the RSL on the other side of the train line, but down here it’s the Sports Club (not to be confused with the Bankstown Sports Hotel nearby), the Oasis Hotel (or the Red Lantern depending on who you ask) or you’re going thirsty.

Those two venues, while fine, are very much products of today’s Bankstown. The Oasis looks like the kind of place you’d hit up to dump some cash into the pokies and have a smoke outside, while the Sports Club has a monopoly on the family friendly crowd. Neither enjoy the kind of maturity conducive to sitting around and making a beer last many hours.

And then there’s the Cumberland Hotel, a proper glimpse into the suburb’s past. If you know Bankstown, you’ll know this venue stands out like the proverbial.

The locals have done their best to incorporate the Cumberland into the street’s mix of fresh food wholesalers, dollar shops and mini marts, but the top half speaks of a time when the working class would need to cool down after a hard day’s work; when a night at the Cumberland might even result in a cheap room upstairs; when Mr. Zhong was still afraid to play with matches.

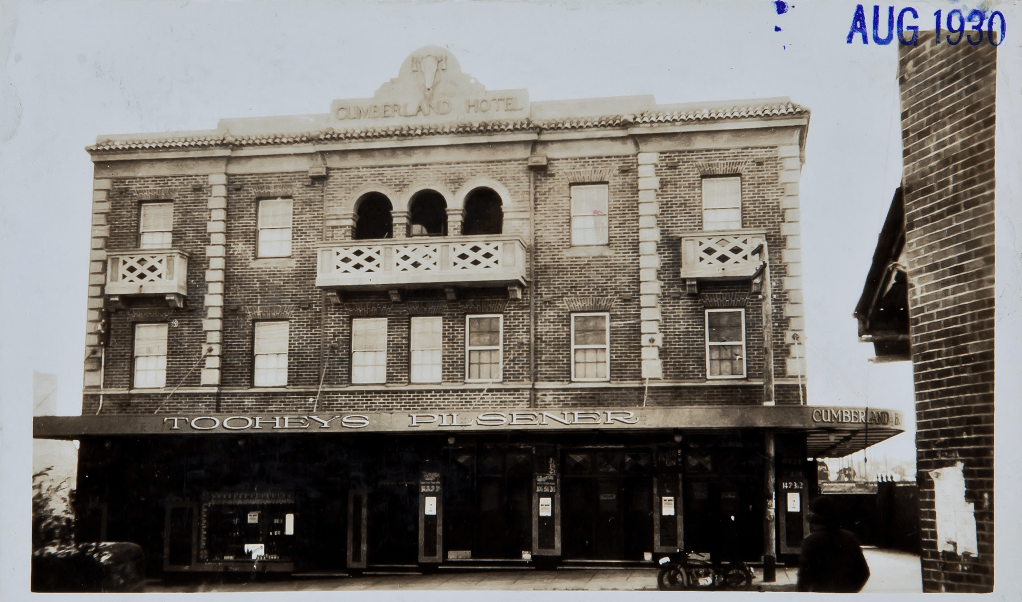

From what I can gather, the Cumberland has its origins in 1929, when William Hoyes, the licensee of the notorious Rydalmere Hotel, transferred that pub’s licence to his newly purchased hotel in Bankstown. The ruckus at Rydalmere, and Hoyes’ hasty escape, seems to have originated in 1907, when a Dundas policeman disturbed a cadre of dudes drinking illegally – at midday! – at the Catholic Church beside the pub.

For his troubles, Constable Howard was bashed quite severely, but got his own back when he shot at the four pissed louts, injuring one of them. Turns out one of them was the hotel’s licensee, while another was the church’s caretaker. You’d think they could have had a quiet one at the hotel itself, but perhaps they had to wash down a communion wafer.

The incident left its mark on the Rydalmere Hotel to the point where even after 22 years, Hoyes opted to take his licence and start over in a suburb less tarnished by violence… for now.

In 1930, the Cumberland was up and running under the watchful eye of Tooheys. Hoyes made way for O’Regan in 1933, who gave it up to O’Reilly in 1934. The names give a clear indication of Bankstown’s cultural background at the time.

Vincent O’Reilly held onto the Cumberland until 1950, by which time the lay of the land had changed quite a bit. The following year the Cumberland Hotel fell under investigation of the Royal Commission on Liquor, which had put old mate Abe Saffron in the hot seat.

Honest Abe had apparently made some licencing deals with several hotels, including the Cumberland, the Morty in Mortdale and the Civic in Pitt Street, that had not impressed the authorities. At the heart of the matter was the improper funneling of booze between pubs under Saffron’s influence, grossly in breach of the Liquor Act.

While all this was going on, the Cumberland endured another parade of licencees including Mr Kornhauser, Mr Norman, Mr Blair and Mr Geoghegan, the latter of which applied for – and received – a 12-month dancing permit in 1957.

During Geoghegan’s tenure, on a momentous November afternoon, a meeting took place that would change New South Wales’ taxi and golf landscapes permanently.

“In November of 1954, three disgruntled members of Campsie Taxi Drivers Golf Club, while having a drink at the Cumberland Hotel in Bankstown, discussed forming a breakaway group of golfers. It wasn’t until after Melbourne Cup Day of that year that a group of up to 10 cabbies decided to form a Taxi Social Golf Club. The first game was held at East Hills Golf Club on the first Tuesday in January 1955.

The foundation meeting was held that day. A foundation committee was elected and Bankstown Taxi Drivers Golf Club was born. Tuesdays were chosen as golf day because back in those days, they were deemed to be the quietest day of the week for cabbies.”

NSW Taxi Golf Association

There it is, folks. Wonder no more. I shouldn’t think there was too much licenced dancing going on that day.

As the 1960s dawned, things changed even further. Geoghegan was out, and in his wake came Masman, Martin, Conlon, Light, Monkey and a switch to decimal currency.

The Oasis had sprung up around the corner, as had the “Bankstown Bowling Club”. In another sign of the times, a TAB in Fetherstone Street, on the other side of the train line, was seen to be impinging upon the Cumberland’s bread and butter. Blair, Heffernan, Davanzo and Lynch would endure this incursion and take the Cumberland into the 1970s.

The beginning of the end came in the 80s, however, when that old undercurrent of pub violence would again raise its ugly head. By that time, Bankstown had become home to two distinct groups of refugees fleeing overseas wars: Lebanese and Vietnamese. They didn’t always gel.

As is now well understood, youth gang crime became an issue for these two ethnic groups. One night, in July of 1986, tensions boiled over in Bankstown. A brawl started outside Bankstown Station and became so violent that wooden palings were torn from fences to be used as weapons.

It’s not hard to imagine these guys hearing of the brawl during a night at the Cumberland and rushing to the aid of their friends. By then, the Cumberland had become “a seedy old watering hole, with a cast of colourful characters, Viet gangsters being shot on the doorstep, topless barmaids, great beers and lots of laughs”. It couldn’t last.

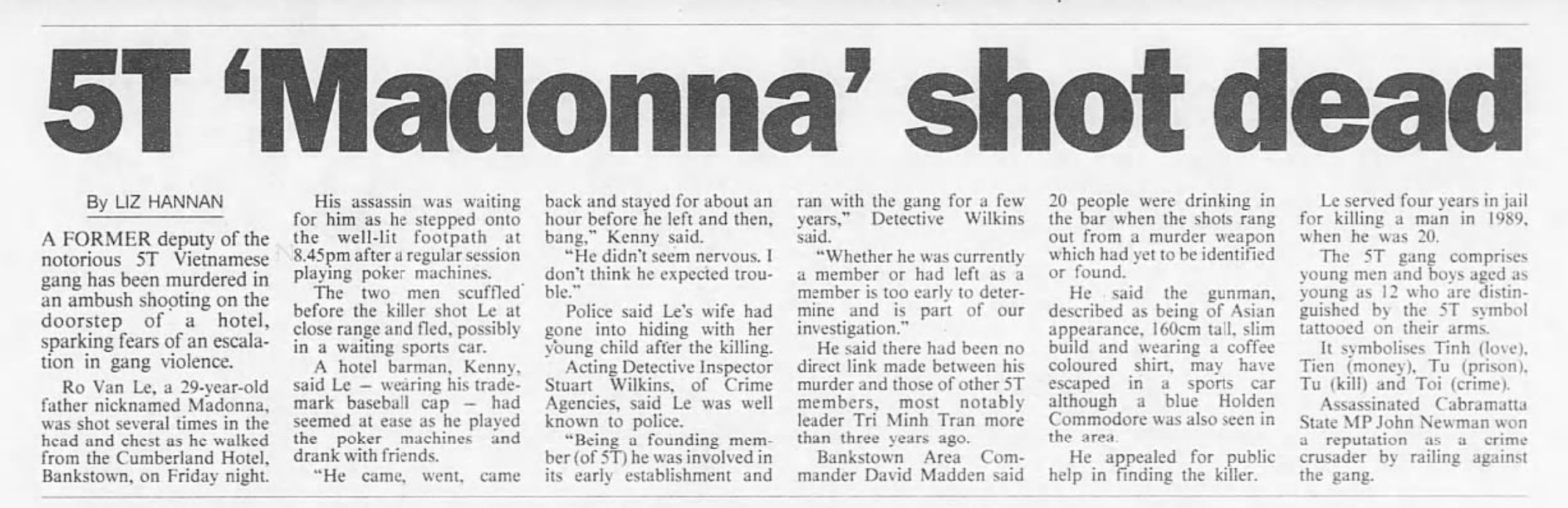

Somehow, the Cumberland staggered into the next decade, which was awash with even more gang violence. Names like 5T and the Madonna Boys should be familiar to anyone who was around at the time. 5T was particularly notorious not only for its violence and clout in the bustling Sydney heroin trade, but for the ridiculous age of its leader, Tri Minh Tran, who took over the gang at 14.

Tran was shot dead in 1995, and gangs such as Red Dragon and the Madonna Boys, led by “Madonna” Ro Van Le, sprung up in the resulting power vacuum. Madonna himself had been convicted of murder in 1989, and a decade later had only just been released from prison when he visited the Cumberland Hotel one Friday night.

It was Madonna’s last. As the drive-by shooter’s bullets entered his head and chest on the footpath outside the Cumberland, they ostensibly ended the hotel as well.

The shooting helped prompt owners Bill and Mario Gravanis to abandon the Cumberland in favour of the Bankstown Sports Hotel further down the road.

Today’s Cumberland is a mix of smaller outlets that have carved up the spacious interior. One must first cross the fruit-laden threshold of TK Plaza…

What was once Madonna’s beloved VIP lounge is likely Skybus Travel, itself no longer in operation if the room full of mangoes and canned squid is anything to go by.

And perhaps the table favoured by those disgruntled cabbie golfers is now a part of Anh Em Quan’s Hot Pot BBQ restaurant. If they’d settled their grievances over a bowl of spicy prawns that day, who knows what kind of world we’d live in now.

Around the back, it’s hard to imagine this was ever a pub. The mural places the Cumberland firmly in the every-second-shop’s-a-fish-market vibe of Old Town Plaza, while the back alley is full of Hiaces rather than getaway cars.

It’s unlikely the Cumberland Hotel will ever serve a cold schooner of beer again. The world that defined the venue is gone. Tooth, Madonna, Constable Howard, the Geoghegans of Bankstown – all are now memories.

At 324, just under the Cumberland’s south wing, the ‘Cumberland Professional Suites’ carry on the name. They probably occupy the rooms upstairs as well, but even they have the sadly familiar For Lease sign outside.

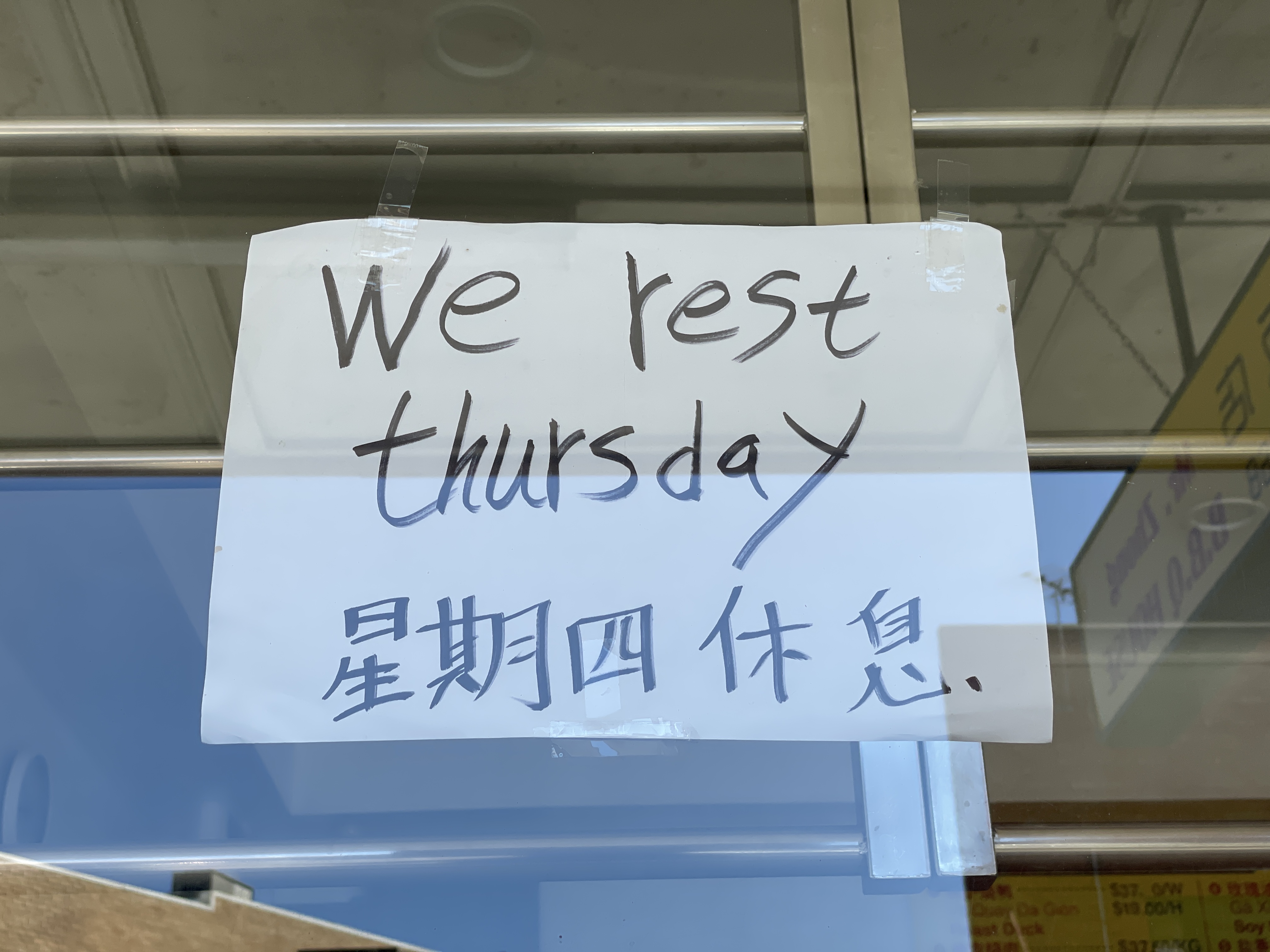

Perhaps the next tenant will take a look at the building’s history and look to maintain some kind of continuity in a way TK and Mr Zhong did not. As I departed fully intact, much to the late Madonna’s envy, I noticed this sign in one of the front windows.

Rest in peace, Cumberland Hotel.

Angelo’s for Hair/For Lease – Belfield, NSW

He came to this country from Europe, in an era that was – in many ways – of greater acceptance than the age we live in today. Barely able to speak the “native” tongue, and still scarred by the horrors of war, he attempted, to the best of his ability, to integrate into the society he found here.

Seriously, imagine the effort: the journey to get to this faraway place is in itself a hellish struggle. And then to arrive, to have to gather your bearings, to learn the language, to assess the social order where almost nobody is like you, and to gauge your place in it.

You don’t know anyone. You have nothing. Nobody is like you, and nobody cares about you.

And after all that, to actually make the effort to insert yourself into that world. To provide for it! With today’s luxuries and privileges, and the world having become a global village, it’s almost impossible to understand that experience.

But he knows.

We’re not talking about an intolerant culture, as we have today. Australia in the post-war era was arrogant, dominant. White Australia, victors of the war in the Pacific, liberator of ‘subordinate’ races found in the occupied island nations.

Today, racial and religious intolerance comes from a place of fear, fear for “our way of life”, fear of the unknown, and a deep-seated, shameful understanding that these ideals are too flimsy to be defended.

But back then, it was an arrogant patronising of these European cultures who had already been brutalised by intolerance beyond understanding. We’ll tolerate your spaghetti and fried rice, fellas.

A people person, he started his career as a hairdresser in the city. Armed with youth, energy, passion, a thirst for knowledge and a hunger for success, he began to network as he plied his trade. The ageing, well-to-do doyennes of Sydney’s east, left alone by their business-minded husbands all day, longed for an outlet for their thoughts, their stories, their plans and their dreams. They found it in him.

And who could blame them? A good-looking, upwardly mobile young man eager to listen while he cuts your hair (all the while learning the intricacies of his new language) would be the perfect ear.

“They were my ladies,” he’d tell me decades later. When I pressed for more, his brow darkened like storm clouds and he shook his head. “Sorry mate, they’re still mine.”

As now, networking paid off. Trust leads to loyalty, and when the young man was ready to move beyond the confines of the department store salon and get his own place, his ladies came with him.

Even though it was out in the wasteland of the south-west, in a tiny suburb few had heard of.

In the mid 1960s, Belfield was still relatively young. We’ve been there before, so there’s no need to go too deeply into the backstory. Catch up first, and then cast our man into the backdrop.

Although it’s the inner-west now, it was truly the outskirts of civilisation for many at the time. Many poor European migrants found themselves in the middle of growing suburbs like Belfield, and often during the worst growing pains. But land was cheap, space was plentiful, and tolerance could be found if you looked past the stares.

He told me the shop had been a deli before he bought it. He’d saved all his income from the city salon, lived hard for years but never let go of the dream to own his own business. The master of his own destiny. We’re content these days to end up wherever life tosses us. Control is too much effort, and believing in fate and destiny means it’s easier to explain away fortune both good and bad. His was a fighter’s generation, and he fought for everything he had. He’d been fighting from the day the Nazis shot his father dead.

His salon fit right into a suburb that had multiculturalised right under the white noses of the residents. An Italian laundry here, a Chinese restaurant (that serves Australian cuisine as well, natch) there, and a Greek hair salon right in the middle.

A friendly, ebullient character, everybody came to know him. The women loved him, the young men respected him, and the old ones still gave him sideways glances. He didn’t care – he’d outlive them.

“I still had my ladies,” he’d recall fifty years later. Some of his city customers had crossed the ditch, but he’d found an all-new community waiting to unload on him. He’d become family as he’d get to know the women, their children, and their children.

I came to this little shop for 25 years to get my hair cut. Always the same style: the Jon Arbuckle. In that time, I went from sitting in the baby chair and chucking a tantrum whenever it was time for a trim, to coming on my own, mainly for the conversation. As the years went on, he revealed more about himself and his life. It fascinated me.

“The hardest part,” he told me the last time I saw him “was that as the years passed, my ladies would…”

He paused. It was difficult.

“They’d stop coming in.”

Very true. Belfield is a very different suburb to what it was even ten years ago, let alone 30. Let alone 50. My grandmother was one of his women, so familiar that it seemed like they’d always be around.

But now she’s gone, and so is he.

“This is it,” he’d said. What? How? Why would you sell?

“I sold years ago,” he confessed. He’d been renting ever since.

I was stunned. Was I destined to never get a haircut again? “You can come to my house if you still want me to cut your hair,” he’d offered, but the look in his eyes suggested we both knew it would never happen. It was a kind gesture, but not the kind you actually take up. No need to be a servant in your own house.

What would he do now? He’d been scaling back the business for a long time. Once, the workload had been heavy enough that he’d hired an assistant, but Toni had long since gone. He’d said he didn’t take new customers anymore, either. It was too hard, pointless to get attached. It was his great strength and his ultimate weakness, that attachment.

So many Saturday mornings I’d spent in that chair, hair down to my shoulders, waiting for my turn. While I waited, he’d chat to me, or Mrs. Braithwaite, or Brett (who’d done time once and it had broken his heart). In all my years of going there I never saw the same “regular” in there twice, such was the expanse of his network.

On that final Saturday, we chatted out the back while he had a smoke. As a kid I’d always wondered about that back area. Turns out it was plastered with pictures of his own kids and grandkids, old salon paraphernalia, photos from his many overseas trips, and a radio constantly blasting ABC 702.

I’d thanked him for the last haircut he’d ever give me, and told him to keep the change. We shook hands, then embraced.

In my youth, I shed many tears in this place in vain attempts to avoid haircuts. As an adult, I shed one more.

The worst part is that two years later, it’s still for lease. I haven’t had a haircut in two years.

Bexley Park Cycles/Nothing – Bexley, NSW