Mecca Cinema/Residential – Kogarah, NSW

For those who’ve just joined us…

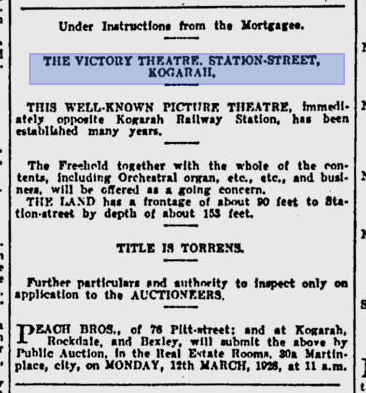

In 1920, the Victory Theatre was built to entertain the rapidly growing population of Kogarah. Just eight years later, however, the victory party was over:

The Victory was purchased by entrepreneur John Wayland, who in 1936 reopened the theatre as…the NEW Victory:

When television entered the picture (so to speak) in the late 1950s, suburban cinemas began to fall off the map rapidly. The fortunes of the Victory (named the Avon by the mid 1960s) were drying up in the face of an uncertain future, and in 1969 Wayland was forced to sell to the Mecca cinema chain, which also owned theatres in Oatley and Hurstville.

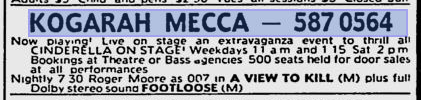

In 1971, owner Philip Doyle rebranded the theatre as the Kogarah Mecca, a name change that tied it to the Hurstville Mecca. The theatre showed a mix of cinematic releases and stage productions, the last of which was a production of Cinderella. Doyle, a would-be impresario, staged and managed the productions himself. Cinderella’s season appears to have begun in 1986:

…and ended in 1989, when Doyle elected to abandon the one-screen format and turn the Mecca into a multiplex. In a futile attempt to compete with the newly opened Greater Union at Hurstville Westfield, which boasted eight screens, Doyle split the Mecca into four new, much smaller screens.

The success of Hurstville Greater Union had also forced Doyle to close the Hurstville Mecca, which was demolished in 1995, leaving Kogarah as Doyle’s focus. Throughout the 1990s, the Kogarah Mecca became known as the cheapest cinema in Sydney, with tickets for at a flat rate of $5.

So there you have it: a cheap cinema running cheap Hollywood entertainment owned by a cheap scumbag in the cheap part of a cheap town. What a legacy.

In 2003, the cinema abruptly and mysteriously closed…which is exactly how Andre and I found it about ten years later.

We’d been intrigued by the taste afforded us during our last visit, and we’d gone back to test the flimsiness of that wooden door on the side. After all, they were only going to demolish the place anyway. What harm could it do to-

Well, whadda ya know? Now there’s no excuse.

We were initially greeted by a storage area. The door had been banging softly in the breeze, and continued to do so after we entered, providing a rough heartbeat for the clutter within. The place was a mess…but what a mess! Relics of the cinema’s history were strewn about the room:

The room itself went right back to the rear of the building. The ducting and pylons built as part of the multiplexing stood out like the proverbial, providing an eerie atmosphere of incongruity. We both agreed there was something not quite right about the place, and it slowly dawned on us we might not be alone.

Surprisingly, the place still had power. Near to where we’d entered, another door yawned open, and the yellow light beyond seemed very inviting. We couldn’t come this far and not continue…

The doorway led to a creepy stairwell, at the top of which was the projection room, and another, more sinister room bathed in a red glow.

The door to this room appeared to have been literally ripped from the wall, and the place was trashed. What had happened here?

The evidence suggested a beer-fuelled rampage by local graffiti artists led by David Brown’s greatest enemy.

The room was full of cinema seats, and by the look of it had perhaps once been some kind of private screening room, or a meeting room. In either case, the interest it provided was limited, and we moved on to the projection room.

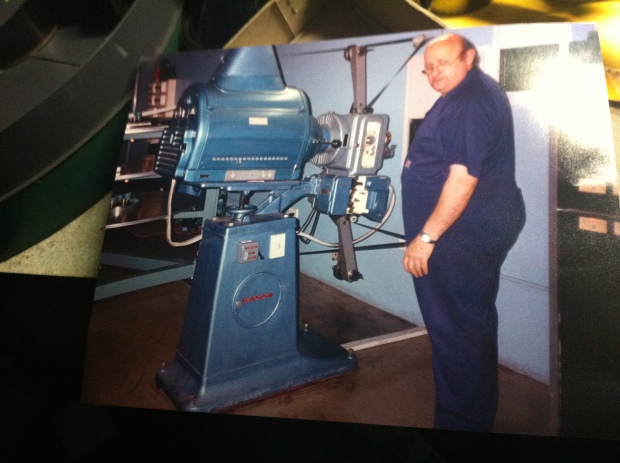

The projection room was somehow in worse shape than the screening room.

What was left of the projectors had been stripped, and equipment lay everywhere. Immediately arresting was a shelf containing scores of film cans filled with cinema advertising…

…and some cryptic words:

It really did look as though the staff just downed tools one day and walked out. If it weren’t for the trashing, it seemed like they could have just walked back in at any minute and started rolling.

The holes in the wall where the projectors had once shone through now provided a view down to the cinemas below…

…at least, enough to know that was our next stop. A stairwell at the rear of the projection room provided the access.

More violence: the door to the foyer appeared to have been forcefully kicked down. Who broke in here? King Leonidas?

The foyer too was the scene of some pretty heavy action. Pepsi cups and popcorn littered the floor, and the door to each cinema hung wide open. In addition to the gaudy pastel art design, Doyle had named each new theatre. We started with the rearmost one, ‘The Ritz’…

And someone had definitely put upon the Ritz. With the seats gone, the room looked a lot larger than it ever had. Enterprising graffiti artists had used a ladder to tag the screen, but apart from that this cinema was probably the least abused of the four.

Not so the ‘Manhattan’, in which our violent predecessors had set up a kind of roundtable. A base of operations? A drinking spot?

It certainly wasn’t to get a better view of the screen, which was no longer in existence.

The chintzy Manhattan skyline which adorned the walls provided a sad framework for the carnage and failure we were witnessing, although the damage was very King Kong-esque.

The ‘Palace’ was palatial as ever with the chairs and screen removed. What’s fascinating is that with the screen removed, it’s easy to see the outline of where the Victory’s grand staircase would have been.

The first cinema, ‘Encore’, was so small that it was hard to imagine it as being adequate for screening anything. I’ve seen bigger home cinema setups than this.

Carpeting the tiny room was a thick pile of movie books, videos, photos and script pages. Some empty removal boxes nearby suggested that the cinema had been used as temporary storage during its last few years.

Back out in the foyer, we were faced with a problem. We had to check out the ticket counter, but the door provided a clear view out to the street. We had to be careful, lest one of the civic-minded locals drop dime on us and end our tour of the Mecca.

No, really?

Hiding out of sight, we crept through the staff office. It was perhaps in the best condition of all of the rooms, with only one major flaw:

The candy bar/ticket counter, when we finally reached it, was just what you’d expect. Condescending signs…

Overpriced refreshments…

And stacks of empty cups, silently waiting to serve their purpose. Bad luck, guys.

I couldn’t help but notice this sign, which I found anomalous. Does Greater Union reserve this right? Does any other cinema? If I’m going to be kicked out of a place, I at the very least expect a reason.

Our earlier fears were unfounded: no one was around. I think we’d been so caught up in the Meccapocalypse that we’d forgotten where we were – the wrong side of Kogarah’s tracks.

Having covered everything, we made our way back to the underground storeroom via the foyer. I was struck by this feature wall. It looks as though the posters are crying, and I don’t blame them after all the hell Doyle had put the place through. If ‘faded glory’ has a visual definition, this is my submission.

As we descended the stairwell to the storeroom, we suddenly became aware just how ornate it was.

The stairs themselves were starting to peel, the cheap paint no longer able to disguise a more regal past.

The stairwell, just like the space upstairs, had been carved up by Doyle in his quest to beat Greater Union at its own game. What had once been a lavish entrance was now just dank storage space for all the grime behind the glitz.

The Celebrity Room snuck up on us. We’d breezed right past it originally, but with a name like that, how had that been possible? Had it even been there the first time?

With hubris set to maximum, Doyle had made the Celebrity Room into his office.

The grimy office was revolting, unkempt, and radiated an enormous sense of unease. It also hid one of the more interesting finds of the entire trip:

If you can ignore the filth for a moment, you can see that the stairs that carried down through the above cinemas would have ended here, and then continued on to the theatre…

But that meant that the original screen was somewhere behind us, in the storeroom. Would anything remain?

On our way back out, we noticed the walls were speckled with (among other things) vintage movie posters. Torture Garden seems particularly appropriate.

If only. Moving on…

At this point, we knew the cinema was deserted. Feeling more comfortable, we resolved to explore the rear of the storeroom, the area which would have sat above the toilet we’d visited last time. It didn’t take long to find the entrance to what had once been the Victory’s stage.

Patient Kogarah audiences had had to put up with no less than four pantomimes during the Mecca years, and there was plenty of evidence of this backstage.

The stage had been bricked over during the multiplexing, but it was all still there.

The pulley system was still in place, though we dared not touch it.

Dated January 1989, this sign advertises the last panto to be staged at the Mecca, and what would have been the last performance ever at the Victory. What a way to go.

Also backstage was the Mecca’s collection of toilets. Who would need this many toilets? And in case you’re sitting there smugly thinking ‘A cinema would need this many toilets, you idiot’, just know that the room they were in wasn’t a bathroom. The room did however feature a variety of pornography featuring plus-sized models affixed to the walls, so maybe the toilets were necessary after all.

Most of the Cinderella props were still backstage, including the carriage…

…and some very bizarre costumes. I don’t know about you, but I don’t remember a giant chicken or Mickey Mouse being in Cinderella.

I wondered if this was the same stage we were standing on at that moment.

The Disneyfied font Doyle had used for his own name, never mind the fact that he was so insistent on ‘family entertainment’, was a sickening touch. There was something not quite right about this whole place, and as we made our way back through the storeroom to leave, we passed plenty more evidence in support of that feeling:

As I mentioned earlier, it seemed like the staff just walked out one day in the middle of work. There had been no effort to clean up the place or to scale it back, like if they’d closed for financial reasons and were preparing to sell. So what had actually happened? The truth is horrific.

Not long after our visit, the scaffolding went up. Despite a few half-hearted protests and calls for the cinema to be revived, it was time for the final curtain.

Flash forward to today.

A gleaming new block of units has replaced the Victory, and all its associated stigma. As I said, there were a few last-minute calls for clemency, and yes, it’s now as bland and faceless as you’d expect, but could you honestly say you’d want to see a movie there again knowing what went on? For the sake of the victims, especially those very brave ones who spoke out, it’s better that no trace has been left behind.

That aside, I think it’s interesting that what was once the suburb’s entertainment hub has been turned into a living space. In a way, it’s a perfect microcosm for how these things work all over the western world.

Picture this: you’re the mayor of a small town or village. You need to attract more people in order to be important, as part of some desperate search for identity, so you permit an attractor: a cinema, a shopping centre, a stadium. But now you’ve built it, and they have come, so where are they going to live? You, in your stately mansion, let the problem build and build, throwing bones where you can. Let’s raze this library, let’s destroy this public pool, but hey, keep the cinema. The locals love that.

More and more people come. They start families. They open businesses. Soon, your town is a municipality, a suburb, a community. And as the towns around it grow at the same rate, your whole area is becoming something much larger than you ever imagined. Suddenly, it’s beyond your control. You were so sure you could keep it under your thumb, get it to your ideal size and then replace the cork. But what happened? Weren’t you the boss?

But the genie is out of the bottle, and he can’t go back in. It’s more than you can handle, and before long, you find yourself replaced by a team, a committee who group-think to make decisions better than you ever could have on your own. Their first decision? “Let’s demolish some of those old businesses and put in a supermarket or two. Ditch that stately manor, the land would be perfect for a car park for the train station. Oh, and knock down that crusty old cinema. We need more living space for our community.”

You really should be thankful. After all, you need a place to live now, right?

Corner Shop/Residential – Merrylands, NSW

Once upon a time, on the corner of Henson Street and Chetwynd Road, Merrylands, there existed a corner shop.

Once upon a time, on the corner of Henson Street and Chetwynd Road, Merrylands, there existed a corner shop. All the locals would journey to the shop whenever they were out of the Big Three: bread, milk, cigarettes. For those who couldn’t make the trip, perhaps those too elderly to easily leave their houses, the shop provided free delivery.

All the locals would journey to the shop whenever they were out of the Big Three: bread, milk, cigarettes. For those who couldn’t make the trip, perhaps those too elderly to easily leave their houses, the shop provided free delivery. In the summertime, on their way to or from the local pool, or maybe just in the midst of riding around the streets on their BMX bikes, kids would stop in for ice cream, or drinks of the icy cold variety.

In the summertime, on their way to or from the local pool, or maybe just in the midst of riding around the streets on their BMX bikes, kids would stop in for ice cream, or drinks of the icy cold variety.  In the 80s specifically, their choice would have been that of the new generation.

In the 80s specifically, their choice would have been that of the new generation. None of that “Good on ya, Mum” nonsense here – strictly Buttercup Bread. Today, the name seems to have disappeared, but it lives on through the ‘Mighty Soft’ brand for those of you interested.

None of that “Good on ya, Mum” nonsense here – strictly Buttercup Bread. Today, the name seems to have disappeared, but it lives on through the ‘Mighty Soft’ brand for those of you interested. Those shelves, once fully stocked to provide a community with the essentials, are now empty. If you imagine it as a metaphor for the emptiness of the concept of community in the modern age, you’ll probably wind up feeling pretty bummed out, so don’t do it.

Those shelves, once fully stocked to provide a community with the essentials, are now empty. If you imagine it as a metaphor for the emptiness of the concept of community in the modern age, you’ll probably wind up feeling pretty bummed out, so don’t do it.

This shop may be confined to Merrylands, but the underlying themes apply to just about every has-been corner shop in any suburb. They’re relics from another era, and one that can never be again.

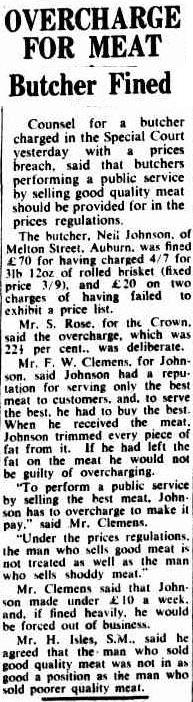

Butcher/Residential – Auburn, NSW

Even the most quiet and unassuming of streets or buildings could have been the site of scandal and intrigue at some point in the past. A little research goes a long way: a quick check of Trove revealed that a street I grew up on was the scene of an inter-war triple murder and several gruesome accidents! It’s the kind of thing that makes for great reading on a cold, rainy afternoon.

So if you live on Melton Street, Auburn, I hope it’s raining right now.

While I’m not going to bother getting into the nitty-gritty of 1950s meat price regulations, the space allotted by the newspaper to the above article should tell you all you need to know about just how important this apparent non-event was.

For this one day, butcher Neil Johnson had his moment in the sun, having been accused of overcharging for meat. In his defence, he claimed that his meat was primo quality, so why shouldn’t he overcharge? The justice system wasn’t convinced, slapping a fine on Johnson that, according to the article, could have forced him out of business. Something certainly did.

Now that you know the story, here’s where it happened. Pastel colours aside, Johnson’s butchery today is completely unassuming. It’s just another ex-corner shop no one gives a damn about. I’m not saying everyone should, but I never cease to find fascination in these little stories that make Sydney’s suburbia more than just a network of streets.

And that’s just what we can see from the outside. Would the interior still be recognisable as a butchery? Does it still carry the stench of Johnson’s failure? Given the current state of Sydney housing prices, they’re questions that for the majority of us will never be answered. Talk about overcharging…

Past/Lives Flashback #1: Union Carbide – Rhodes, NSW

Original article: Timbrol Chemicals/Union Carbide/Residential – Rhodes, NSW

Yes, the time has finally come. The most popular entry on Past/Lives over the last year (and a bit, by this point) by far was the tragic tale of Rhodes and that most toxic tenant, Union Carbide. Rhodes’ decimation at the hands of industrial abuse throughout the 20th century and subsequent resurrection as a residential paradise in the 21st is a long story, and one with repercussions for the whole of Sydney even today. Grab a coffee (although Rhodes residents, maybe don’t use tap water) and get comfortable…we’ll be going back over the whole thing.

THEN

Rhodes Hall, near Leeds, was about as far from the eastern shore of the picturesque Homebush Bay as Thomas Walker could imagine. A commissary, Walker had arrived at Port Jackson in 1818, and the following year bought an allotment of land from Frederick Meredith, another early settler. Walker built a house on his bank of the Parramatta River, naming it Rhodes after his grandmother’s estate back in the motherland because even hardened and worldly mercenaries still have soft spots for their grannies. So soft, in fact, that in 1832, Walker moved to Tasmania where he built another estate…also named Rhodes. She must have spoiled that kid rotten.

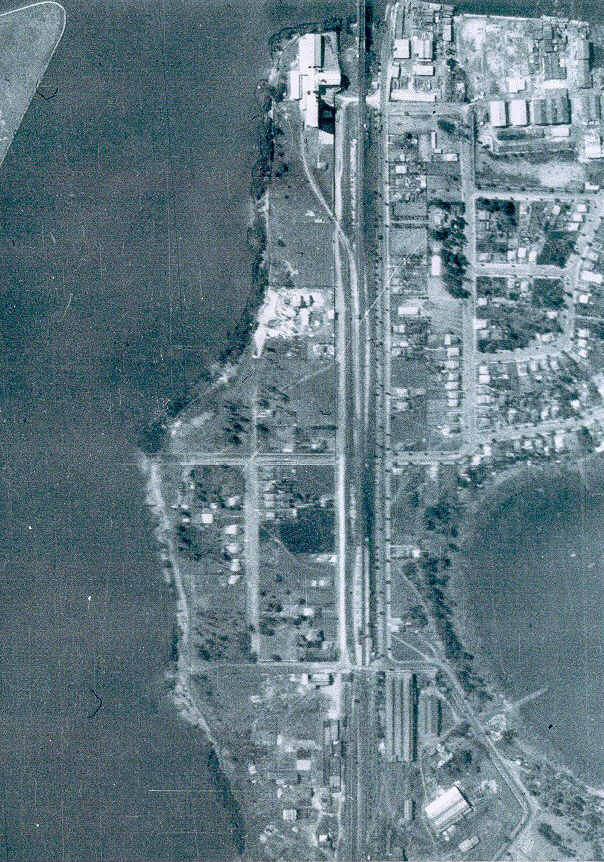

The Walker family relinquished their control over the Rhodes estate in 1919, when they sold up to the John Darling Flour Mill. By this point, Rhodes was no stranger to industry. Eight years earlier, G & C Hoskins had cleared much of the area’s forests to erect a cast iron foundry, and once this had happened, everyone got on board. There was little resistance to this kind of heavy industrialisation, especially in a suburb like Rhodes, which was easily accessible by rail and water.

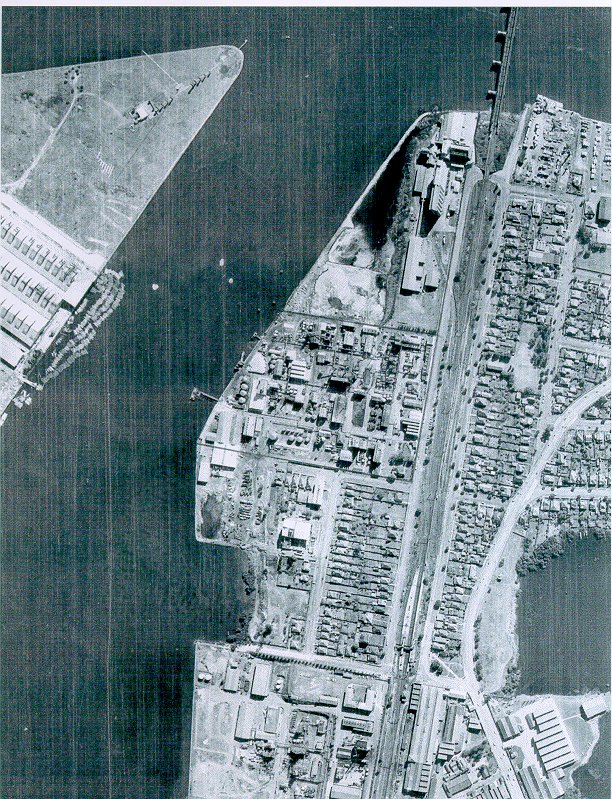

Kind of looks like the silhouette of a guy with a ponytail, doesn’t it? Image courtesy City of Canada Bay.

At this point in time, Rhodes and the neighbouring Homebush were the outer limits, truly the Western Suburbs, with only Parramatta and the Blue Mountains more forbidding. Sydneysiders were keen to get the blossoming industrial sector as far away from their own backyards as possible (understandably), and Rhodes, bordered by the new abattoir and the Parramatta River, was out of sight, out of mind.

Flour mills and cast iron foundries weren’t exactly environmentally friendly (a phrase not yet in use in 1928), but the true damage to Rhodes didn’t begin until the arrival of Timbrol Ltd in 1928. Timbrol had been established in 1925 by three Sydney University researchers keen to manufacture their own brand of timber preservative, so at least it was all for a good cause.

In 1933, Timbrol had a breakthrough! It was able to produce the first Australian made xanthates, which is used in the mining sector for extracting particular kinds of ores. With the advent of the Second World War, xanthate exports boomed, and expansion of the Timbrol site was required. But where to go? Sandwiched between the train line and the foreshore, and with John Darling to the north and CSR (another booming wartime chemical company) to the south, Timbrol was apparently out of options.

Just joking. Of course there was an option – the only option: reclaim land from Homebush Bay by filling in the river with contaminated by-products and building over it. Out of sight, out of mind.

The post-war housing boom brought about various new challenges in the domestic domain, most of which could be easily solved with chemicals. Thus, demand for chlorine, herbicides and insecticides, particularly DDT, skyrocketed, and Timbrol was right there to capitalise. And by right there, I mean jutting out over Homebush Bay on new, hastily constructed ground.

Spurring the chemical company’s efforts on even further were their competitors CSR, ICI and Monsanto, most of whom were a stone’s throw away from the Timbrol site. The close proximity of these companies meant that the output of potentially dangerous by-product seemed minimised in the eyes of the era’s governments; it was better for all the companies to be dumping together rather than dumping apart at wider intervals. This also meant that the neighbouring sites could ‘borrow’ Timbrol’s approach to expansion – good news for Homebush Bay.

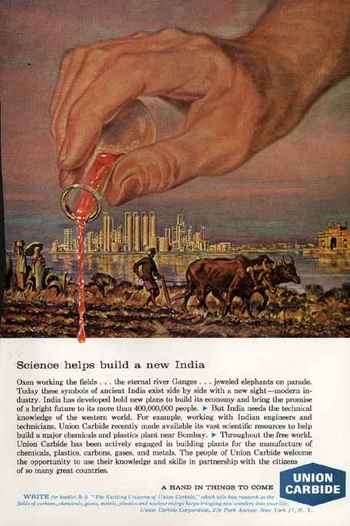

Timbrol’s success had attracted another element: the American chemical giant Union Carbide, which saw Timbrol as a great place to start an Australian subsidiary. Union Carbide dated back to 1898, and had built its wealth through aluminium production and its zinc chloride battery arm – both of which seem like the perfect thing to manufacture on the bank of a serene body of water.

At this point I’d like to pose a question: when did it ever seem like a good idea to produce chemicals like herbicides, zinc chloride and xanthates beside a healthy bay full of wildlife? Who signed off on this? How were the guys in charge of these companies able to look at this beautiful place and think “Hmm, needs more poison.”? I’m aware that without these chemicals we wouldn’t be able to live the way we do today, but some of these decisions were bordering on just straight up evil.

The arrival of Union Carbide frightened Timbrol’s competitors. The might of the American parent company meant near-unlimited resources, so local campaigns were stepped up.

CSR and even old John Darling began to encroach upon the bay, re-sculpting the landscape as they saw fit.

The initial success of Union Carbide Australia didn’t go unnoticed overseas, either. Associated British Foods bought John Darling’s Flour Mill for its Australian subsidiary Allied Mills in 1960, rebranding it Allied Feeds. Most of the product manufactured at the Allied Feeds site would end up in the stomachs of livestock sent to Homebush Abattoir, where said stomachs would then be carved up to be fed back to the populace. And for that, you need MORE ROOM.

But back to Union Carbide. The early 1960s weren’t kind to UC. Competitors and waning demand had teamed up to diminish the brand, but that didn’t stop the near endless flow of poisons into the bay. By now, nearly all of Union Carbide’s output produced an unfortunate and extremely unpleasant by-product: dioxins. Highly toxic and capable of, at the very least, causing cancer and damaging reproductive and immune systems, dioxins are usually exposed to humans via food particularly meat and fish. What a great idea then to produce extremely unsafe levels of dioxins right beside a manufacturer of animal feed. What a great idea to produce that animal feed on top of land infused with dioxins. What a great idea to expel those unwanted dioxins into Homebush Bay, a waterway directly linked to Sydney Harbour and full of fish.

Let’s take a moment to hear from the World Health Organisation about dioxins:

Short-term exposure of humans to high levels of dioxins may result in skin lesions, such as chloracne and patchy darkening of the skin, and altered liver function. Long-term exposure is linked to impairment of the immune system, the developing nervous system, the endocrine system and reproductive functions. Chronic exposure of animals to dioxins has resulted in several types of cancer. Due to the omnipresence of dioxins, all people have background exposure and a certain level of dioxins in the body, leading to the so-called body burden. Current normal background exposure is not expected to affect human health on average. However, due to the high toxic potential of this class of compounds, efforts need to be undertaken to reduce current background exposure.

So…don’t do what Union Carbide did next, then?

The fortunes of Union Carbide Australia were reversed by the Vietnam War. See, Vietnam has a lot of jungles, and those pesky Vietcong kept hiding in those jungles, so what better way to flush them out than by removing their hiding spot? Union Carbide was contracted by the US military to produce Agent Orange, a dioxide-heavy defoliant. Even when it was discovered that Agent Orange’s components contained a particularly toxic strain of dioxin, it continued to be sprayed indiscriminately throughout the war, during which dioxins continued to be dumped into Homebush Bay.

In the midst of all this, Union Carbide research scientist Douglas Lyons Ford invented Glad Wrap at the Rhodes plant. It was introduced to the Australian market in 1966, the first such product in the country. Well, that kind of balances out that other thing, doesn’t it?

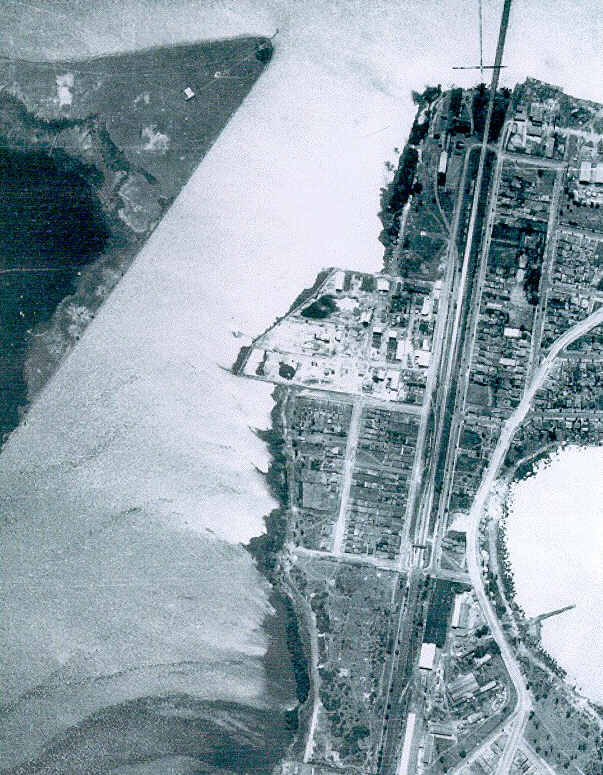

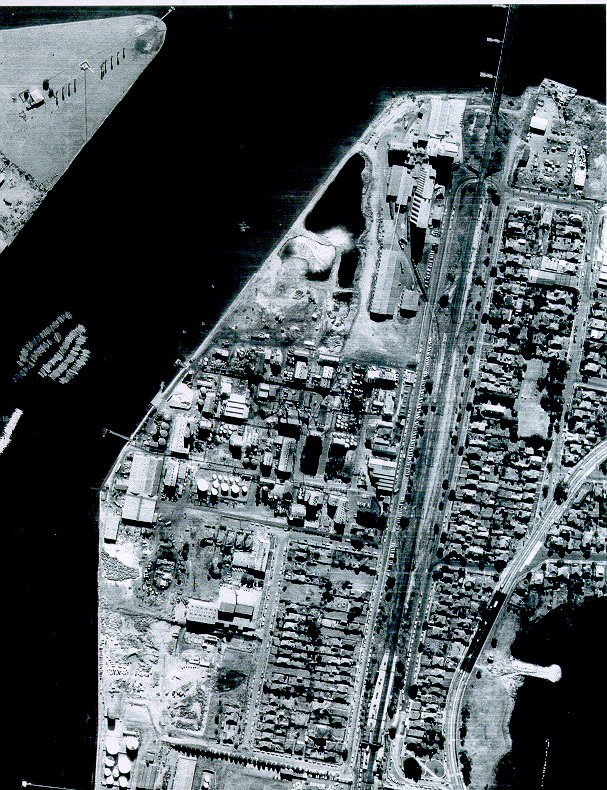

By the 70s, environmental action against companies like these was stepping up, and the population of Sydney had exploded westward. Rhodes’ train line was now a sharp divider between the industrial zone and a booming residential sector.

Further north and across the river, Meadowbank and Ryde were both beginning to cast aside their industrial legacies and welcoming more and more families, while to the south, the Homebush Abattoir was winding down operations. Forward-thinking residential developers were eyeing these areas with great interest, and keeping government wheels greased to ensure their availability in the future. In typical lightning fast Sydney reaction time, this movement was accommodated in the mid-80s by the construction of Homebush Bay Drive, a highway that bypassed the nearby suburb of Concord and tracked through Rhodes’ industrial zone. Out of sight, out of mind.

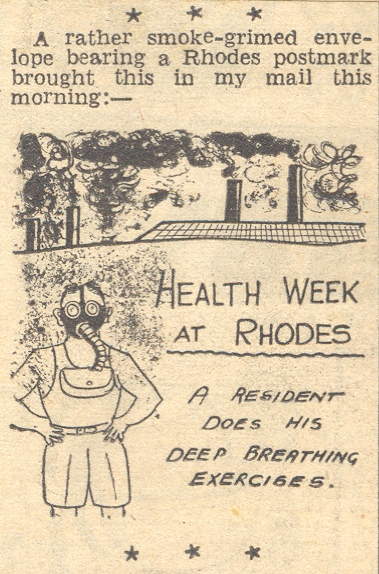

By the early 1980s, Rhodes was known throughout the land for its toxicity and odour above all else.

Its rich legacy of achievements in the field of chemistry long forgotten, Union Carbide was looking increasingly sick and tired; a relic of another age. But one major incident in 1984 made it look downright villainous.

In December of that year, an explosion at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India exposed half a million people to toxic gases, killing thousands. PR disaster for UC, and the final straw for the parent company. Most of its international subsidiaries were wound up in the years following Bhopal, including the Rhodes plant, which ceased operations in 1985. Allowed to leave without any kind of cleanup effort, Union Carbide left behind a toxic legacy that remains detrimental to Sydney today.

The NSW Government and the Australian Olympic Committee had hoped to transform Rhodes into an Olympic athlete village by the 2000 Sydney games, but they had underestimated just how poisoned the land was.

Government remediation efforts tried in vain between 1988 and 1993 to heal the land, but it wasn’t until 2005, long after the end of the Olympics, that private enterprise intervene with the necessary money and technology to properly clean the land. Why this sudden burst of effective effort so long after the fact?

NOW

Today, if you turn off Homebush Bay Drive at the IKEA, you’ll descend into valleys of glass and steel. Rhodes’ rebirth as a gauntlet of residential and commercial towers, a process which began in 2005, is nearly complete. Sensing an opportunity to make money, Mirvac and other developers pounced on the toxic wasteland at the end of the 90s, saving it from a future of causing people to hold their breath as they drove past.

With a steady flow of money and the promise of even more at the end of the remediation rainbow, Thiess and the NSW Government got to work turning the poisonous dirt into the foundations of the futuristic castles that line the foreshore today.

But while the reclaimed land has been mostly made harmless, the bay has not. In fact, the NSW Department of Health has prohibited fishing west of Sydney Harbour Bridge due to an abundance of dioxins. And swimming? Forget it.

The remediation efforts have been effective in more ways than one. I don’t think that Mirvac and friends really cared about anything other than making the land safe enough to pass re-zoning as residential, but despite this, wetland wildlife has begun to return to the bay. Studies on the sea life are ongoing with hopes that one day the bay will once again be safe, but I don’t think we’ll see it in our lifetime. To my infant readers: this means you too.

To the developers’ credit, the project seems to have largely been a great success. There’s the popular shopping centre, complete with cinema and IKEA (a huge coup in its day, since superseded by Tempe), and Liberty Grove to the east. Care has been taken to eradicate most traces of the industrial nightmare of the past. The new units look good enough to stop you from wondering why the grass is always yellow, and they’re certainly filling up fast. And yet…

If you plant a seed in bad soil, it won’t grow very well. Case in point: this is the unit tower being constructed directly upon the former Union Carbide site. Every other tower in Rhodes is either completed or is only weeks away, but not Union Carbide. In fact, the entire site seems to have been plagued with construction delays or other issues. Sure, this stage of the Rhodes project started later than the others, but that too is down to the sheer toxicity of the Union Carbide land.

At the rear, things look even worse. Piles of dirt sit around, uglifying the scenery. Cranes hover above the unfinished structure like buzzards.

On the corner of Shoreline and Timbrol, construction equipment is a mainstay. It’s as if they just can’t make this one happen, despite their money and intentions.

Tower number two hasn’t even started yet, acting as a base of operations for the workers completing tower number one. In 1997, Greenpeace discovered 36 sealed drums of toxic waste underneath the Union Carbide site, so there’s no telling what these guys are digging up as they go. Does your underground carpark glow in the dark?

Down at the Union Carbide foreshore, an even eerier sight: completed units, completely empty.

These seem to be ready to go, but either due to environmental concerns or the noise of construction, residents aren’t allowed to move in yet. I’d be leaning toward the former reason, seeing as plenty of other people here have to put up with the noise.

The Rhodes experiment has proven to be an environmental triumph, arguably even greater than Sydney Olympic Park, but it’s an even greater financial triumph. The corporations behind the remediation weren’t doing this for the sake of the environment or because they felt like doing something nice, they were doing it for the exact same reason the land was stained in the first place. Rhodes may have gotten the second chance Bhopal never did, but they’re equally valid testaments to that reason.