Shea’s Creek/Alexandra Canal – Mascot, St Peters, Alexandria NSW

You’re looking at Sydney’s most polluted waterway. And I thought Rhodes was bad.

In the late 1880s (it’s always the 80s), someone envisaged a grand canal stretching from Botany Bay to Sydney Harbour. It would start at the Botany Bay end of the Cooks River, and lead all the way through the city before opening up at Circular Quay, thereby giving the Eastern Suburbs the island refuge from the great unwashed they’ve always wanted. To that end, I’m surprised it never happened.

Shea’s Creek, a small offshoot of the Cooks River, was chosen as ground zero for the new tributary, which was supposed to act as an access route for barges to transport goods between the multitude of factories set up along the creek in the area. Factories including brickworks, tanneries and foundries. Factories that drained their runoff directly into the canal. A canal that is, according to the EPA, “the most severely contaminated canal in the southern hemisphere”. So keen to pollute were the industrial warlords of yesteryear that they had to invent waterways to defile.

At the time the canal was constructed, Sydney’s roads were a terrible mess completely unsuitable for transporting goods, making an aquatic access route more practical. Thankfully, Sydney’s roads today…uh…they…they’re pretty uh…let’s get more canals happening.

Between 1887 and 1900, Shea’s Creek was ripped up and turned into the canal. By 1895 it was looking unlikely that it would ever reach Sydney Harbour. The NSW Government had decided that as a sewer, the Shea’s Creek Canal as it was known then was doing a good enough job as a carrier of stormwater and runoff, and that there probably wouldn’t be a need to spend all those pounds carrying on with the project. Tenders were called again to complete the canal in 1905, but there were no takers.

The canal was renamed the Alexandra Canal in 1902, after the then-Queen Consort Alexandra. Coincidentally, the suburb that the canal ended in, Alexandria, was also named for her. I bet she was proud, too.

This is how it ends. The mighty canal winds down to a stormwater drain, which then continues to wind up through Alexandria before disappearing. Apparently, the cost of the already 4km canal was so prohibitive as to cancel the rest of the project. It might also have been that the powers that be were trying to save lives, for in creating the Alexandra Canal, they had also created…a bloodthirsty monster!

There have been several attempts since 1998 to clean up the canal, add cycleways (more cycleways!), cafes and restaurants, and generally make it a nice place to be.

As you can see, it hasn’t happened yet. Maybe when the city’s insane lust for cycleways finally stretches the canal to Sydney Harbour, that fantasy can be realised.

Bank of Australasia/3 Wise Monkeys – Sydney, NSW

The Bank of Australasia first moved into this address in 1879, establishing their ‘Southern Sydney’ branch in a rented building. The current building was erected in 1886, but remained under the ownership of the Estate of a James Powell until 1902, when the BOA suddenly remembered it was a bank and could take any property it wanted. It bought out the site, which remained a bank until 1998. The Bank of Australasia became a part of the ANZ in 1951, and rebranded this site as an ANZ bank in 1970.

Although the interiors have been refurbished, the exterior of the building is in remarkably good condition considering what the site is now – the 3 Wise Monkeys pub. Established in 2000, the 3 Wise Monkeys has a reputation as a live music venue and as a place where wisdom is not on tap. Of all the places in Sydney to not want to be seeing, hearing or speaking evil, George Street is probably at the top of the list.

Yasmar – Ashfield, NSW

As you crawl along Parramatta Road, past the Vita Weat building, the Strathfield Burwood Evening College, the Homebush Racecourse, the Midnight Star, the Silk Road, the Brescia showroom and Chevy’s Ribs, you might notice these forbidding gates peeking out from behind a near-impenetrable wall of bushes. On a road full of head-turners and eye-catchers, a true time warp awaits the hand of progress to seize it by the overgrown scruff of its neck and haul it into the 21st century.

It can wait a little longer while we take a look. After all, it’s only existed in its present state for over 150 years.

The unusual name of Yasmar originated in 1856, when Haberfield landowner Alexander Learmonth erected his home on the estate, which he had inherited through marriage to the granddaughter of ubiquitous Sydney property tycoon Simeon Lord. Learmonth named the house Yasmar after his father-in-law, a Dr. David Ramsay. Surrounding Yasmar House was a magnificent garden, designed in the Georgian fashion to gradually reveal and present the house.

Very gradually, clearly.

In 1904, the property was leased by Grace Brother Joseph Grace, and became his Xanadu. Fittingly, Citizen Grace died in the house in 1911. The estate fell into the hands of the NSW Government in 1944, who promptly proceeded to establish a centre for juvenile justice on site.

When it dawned on the powers-that-be that years of horticultural neglect had created the Alcatraz-style escape proof prison seen today, the estate was turned into a juvenile detention centre, which lasted from 1981 to 1994, when the Department for Juvenile Justice relocated, presumably using machetes. From then until 2006, the grounds housed NSW’s only female juvenile justice centre, and since that time, politicians have argued back and forth to have Yasmar made available to the public.

These days, it appears that Yasmar is used as a government training facility. The entrance is around the side in Chandos Street, giving visitors a sense of the sheer scale of the site.

Seeing as the gate was open, I went right in, ignoring the deterrent magpies perched threateningly in nearby trees.

Yasmar’s gardens are huge, but much is now taken up by the training and detention facilities. The open day held in late July allowed visitors a rare look around the grounds and inside the house. What’s that? You didn’t make it? Lucky for you I was there. Read on…

It’s believed that this may have been Australia’s first ever swimming pool, but a more common theory is that it acted as a sunken garden. Either way, it had long since fallen into dereliction by the time I got to have a look.

The view from the inside. There have only been a handful of open days held here since the early 90s, and this year’s was the first since 2007, so this isn’t a view many people get. It’s…great.

Through the thick foliage you can see the various detention and training facilities located around the grounds.

A better view of the house itself. It’s not all that impressive on the outside. I was expecting something grander. Inside, however…

…it’s still just an old house. No, it’s actually fascinating in its own ancient way, and the weight of history here is pretty hefty. Many of those visiting for the open day were former inmates. One hadn’t lost his rebellious nature at all over the years, ducking under the ‘do not cross’ tape to venture deeper into the house before being shouted at by the supervisor. The system doesn’t work.

You wonder just how much they cared about child welfare back then.

Out in the courtyard it’s pretty bleak. Though they did have one great feature I’m consistently a sucker for:

Yes, that’s right. The door to nowhere.

What’s also notable is the nearby Yasmar Avenue, further adding to the sense of entrenchment of the estate within the Ashfield area.

Although neglected and misunderstood like so many of its inmates, Yasmar, Sydney’s Mayerling, exists as a unique example of a 19th century estate virtually unchanged since its establishment. While governments and councils have fooled around for decades over Yasmar’s fate, the estate itself has become an integral part of the Parramatta Road experience. In its current state, it is to Parramatta Road what that ancient expired carton of milk is to your fridge – an indicator of just how bad a housekeeper you are.

For more on the illustrious history of Yasmar, check out Sue Jackson-Stepowski’s excellent write-up here.

Homebush Racecourse/Horse & Jockey Hotel – Homebush, NSW

Operating between 1841 and 1859, Homebush Racecourse was Sydney’s premier horseracing venue. It was located on the Wentworth Estate in the Homebush area, and stood in the approximate area encompassing the corner of today’s Underwood and Parramatta Roads. When Randwick Racecourse opened in 1859, it superseded Homebush’s track, causing the latter to fall into a period of dereliction, although it still operated as a track until 1880. A man’s body was found on the course in 1860, the grandstand spectacularly burned down in 1869, and throughout the 1870s it was used for human running races. When the Homebush Abattoir was established in 1915, the site of the racecourse was employed as the slaughterhouse saleyards.

The only evidence that horseracing ever took place in the area is this pub, located along Parramatta Road, east of Underwood Road. The Horse & Jockey Hotel itself has a colourful history – it was originally the Half Way Hotel, named for its location halfway between the city and Parramatta. The site of the death of Australia’s first bushranger, and once patronised by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, the original hotel changed its name for the establishment of the racecourse (which it overlooked), and was the site of the inquest into the 1869 grandstand fire. Rebuilt beside its original site in 1876, the pub itself burned down in the early 1920s. It was rebuilt again in its present form soon after and remains as the only reminder of Homebush’s racing days.

Old Burial Ground/Sydney Town Hall – Sydney, NSW

George Street, 1844. Burial ground on the left. Image courtesy State Library NSW DG SV*/Sp Coll/Rae/7.

Considered the outskirts of town in 1792, the site at the corner of George and Druitt Streets in Sydney was chosen by Governor Arthur Phillip to be the colony of New South Wales’ primary burial ground. By 1820, however, the cemetery had become full, and was closed as a result. It fell into a period of dereliction and neglect, gaining a reputation as a place to avoid, especially on hot days and at night.

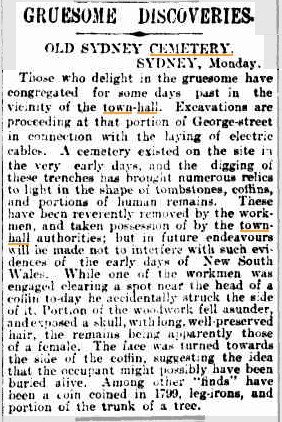

Sydney had grown exponentially by the 1840s, and it had been suggested that the burial ground be used as the site of a town hall for Sydney. Despite vehement opposition in some sectors…

…plans went ahead. The Sydney City Council applied for and received a grant of a portion of the burial ground in 1865. Reinterment of the bodies took place in 1869, with most moved to Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney’s west. Most…

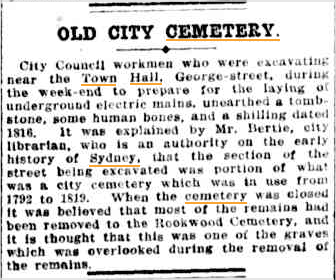

More graves were found in 1974, 1991, 2003, and as recently as 2008:

At the very least, the extreme amount of bodies left at the site ensured high turnout numbers for Town Hall events.

There is little on the site today to recognise the site’s former life as a cemetery. I guess they thought that since there were so many bodies left behind, they didn’t need one. Still, in this small, dank alcove which reeks of piss, there’s a tiny reminder:

It reads:

This plaque is dedicated to the memory of those who arrived in this country with Captain Arthur Phillip on the First Fleet in 1788 and were buried nearby.

-Fellowship of First Fleeters, 1988

“Were“? Still, Town Hall can take comfort in the fact it’s not the only former burial ground site used by a major Sydney landmark today. Yes, like Weekend at Bernie’s II, they did it again…