Yasmar – Ashfield, NSW

As you crawl along Parramatta Road, past the Vita Weat building, the Strathfield Burwood Evening College, the Homebush Racecourse, the Midnight Star, the Silk Road, the Brescia showroom and Chevy’s Ribs, you might notice these forbidding gates peeking out from behind a near-impenetrable wall of bushes. On a road full of head-turners and eye-catchers, a true time warp awaits the hand of progress to seize it by the overgrown scruff of its neck and haul it into the 21st century.

It can wait a little longer while we take a look. After all, it’s only existed in its present state for over 150 years.

The unusual name of Yasmar originated in 1856, when Haberfield landowner Alexander Learmonth erected his home on the estate, which he had inherited through marriage to the granddaughter of ubiquitous Sydney property tycoon Simeon Lord. Learmonth named the house Yasmar after his father-in-law, a Dr. David Ramsay. Surrounding Yasmar House was a magnificent garden, designed in the Georgian fashion to gradually reveal and present the house.

Very gradually, clearly.

In 1904, the property was leased by Grace Brother Joseph Grace, and became his Xanadu. Fittingly, Citizen Grace died in the house in 1911. The estate fell into the hands of the NSW Government in 1944, who promptly proceeded to establish a centre for juvenile justice on site.

When it dawned on the powers-that-be that years of horticultural neglect had created the Alcatraz-style escape proof prison seen today, the estate was turned into a juvenile detention centre, which lasted from 1981 to 1994, when the Department for Juvenile Justice relocated, presumably using machetes. From then until 2006, the grounds housed NSW’s only female juvenile justice centre, and since that time, politicians have argued back and forth to have Yasmar made available to the public.

These days, it appears that Yasmar is used as a government training facility. The entrance is around the side in Chandos Street, giving visitors a sense of the sheer scale of the site.

Seeing as the gate was open, I went right in, ignoring the deterrent magpies perched threateningly in nearby trees.

Yasmar’s gardens are huge, but much is now taken up by the training and detention facilities. The open day held in late July allowed visitors a rare look around the grounds and inside the house. What’s that? You didn’t make it? Lucky for you I was there. Read on…

It’s believed that this may have been Australia’s first ever swimming pool, but a more common theory is that it acted as a sunken garden. Either way, it had long since fallen into dereliction by the time I got to have a look.

The view from the inside. There have only been a handful of open days held here since the early 90s, and this year’s was the first since 2007, so this isn’t a view many people get. It’s…great.

Through the thick foliage you can see the various detention and training facilities located around the grounds.

A better view of the house itself. It’s not all that impressive on the outside. I was expecting something grander. Inside, however…

…it’s still just an old house. No, it’s actually fascinating in its own ancient way, and the weight of history here is pretty hefty. Many of those visiting for the open day were former inmates. One hadn’t lost his rebellious nature at all over the years, ducking under the ‘do not cross’ tape to venture deeper into the house before being shouted at by the supervisor. The system doesn’t work.

You wonder just how much they cared about child welfare back then.

Out in the courtyard it’s pretty bleak. Though they did have one great feature I’m consistently a sucker for:

Yes, that’s right. The door to nowhere.

What’s also notable is the nearby Yasmar Avenue, further adding to the sense of entrenchment of the estate within the Ashfield area.

Although neglected and misunderstood like so many of its inmates, Yasmar, Sydney’s Mayerling, exists as a unique example of a 19th century estate virtually unchanged since its establishment. While governments and councils have fooled around for decades over Yasmar’s fate, the estate itself has become an integral part of the Parramatta Road experience. In its current state, it is to Parramatta Road what that ancient expired carton of milk is to your fridge – an indicator of just how bad a housekeeper you are.

For more on the illustrious history of Yasmar, check out Sue Jackson-Stepowski’s excellent write-up here.

Rhodes Public School/Rhodes Community Centre – Rhodes, NSW

This building served the community of Rhodes from 1922, when the suburb was only mildly polluted, to 1993, when it glowed in the dark. Continuing in its tradition of making smart choices for the Rhodes area, the NSW Government sold the school to the Canada Bay Council, which has used it as a community centre ever since. Amusingly and unsurprisingly, most of the school amenities are still in place, including the loudspeaker under the roof.

It’s strange to see a school without the Building Education Revolution scheme’s signature flimsy, tacked on buildings. The problem the Rhodes community now faces is where their three-headed children will go to school. All the local schools have filled up rapidly since the area became residential, forcing parents to send their children further away from Rhodes for their education. Given what we know, is that really such a bad thing?

Old Burial Ground/Sydney Town Hall – Sydney, NSW

George Street, 1844. Burial ground on the left. Image courtesy State Library NSW DG SV*/Sp Coll/Rae/7.

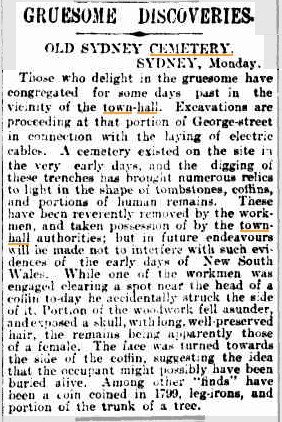

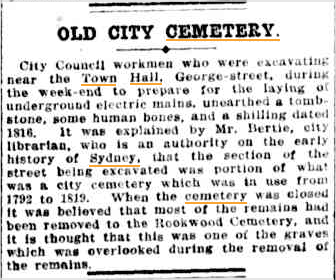

Considered the outskirts of town in 1792, the site at the corner of George and Druitt Streets in Sydney was chosen by Governor Arthur Phillip to be the colony of New South Wales’ primary burial ground. By 1820, however, the cemetery had become full, and was closed as a result. It fell into a period of dereliction and neglect, gaining a reputation as a place to avoid, especially on hot days and at night.

Sydney had grown exponentially by the 1840s, and it had been suggested that the burial ground be used as the site of a town hall for Sydney. Despite vehement opposition in some sectors…

…plans went ahead. The Sydney City Council applied for and received a grant of a portion of the burial ground in 1865. Reinterment of the bodies took place in 1869, with most moved to Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney’s west. Most…

More graves were found in 1974, 1991, 2003, and as recently as 2008:

At the very least, the extreme amount of bodies left at the site ensured high turnout numbers for Town Hall events.

There is little on the site today to recognise the site’s former life as a cemetery. I guess they thought that since there were so many bodies left behind, they didn’t need one. Still, in this small, dank alcove which reeks of piss, there’s a tiny reminder:

It reads:

This plaque is dedicated to the memory of those who arrived in this country with Captain Arthur Phillip on the First Fleet in 1788 and were buried nearby.

-Fellowship of First Fleeters, 1988

“Were“? Still, Town Hall can take comfort in the fact it’s not the only former burial ground site used by a major Sydney landmark today. Yes, like Weekend at Bernie’s II, they did it again…

Garden Palace/Royal Botanic Gardens – Sydney, NSW

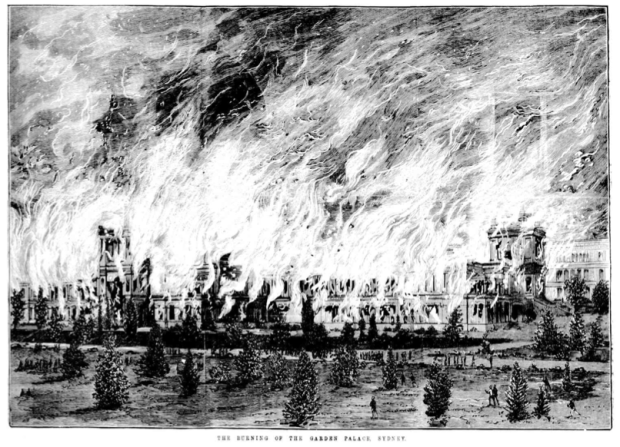

In 1877, the Royal Agricultural Society of NSW decided to stage an international exhibition. As planning commenced, it became clear that the Intercolonial Exhibition Building in Prince Alfred Park wasn’t going to cut it as a venue. After applying some pressure on the NSW Government, which did not want to appear foolish on the world stage, money found its way to the right place, and the enormous Garden Palace was built in the Royal Botanic Gardens in only eight months, just in time for the exhibition.

The building featured restaurants, tea rooms, a fountain, and yet another statue of Queen Victoria. It contained the city’s first hydraulic lift (they really loved their hydraulic lifts back then, didn’t they?). It also boasted primarily timber architecture, which didn’t work out so well.

In late September, 1882, the Palace caught fire and burned to the ground. The cause of the blaze has never been established, but in the years following the International Exhibition, there was much consternation about what purpose the Palace would then serve. All I’m saying is, I’m sure there were a few people not sad to see it go. Mourners of the Palace seemed to be most upset by the wastefulness of it all, and by 1890 it had largely been forgotten.

These gates are the only reminder that it was ever there, despite having been erected in 1889 to commemorate the Palace. So wait, people were upset about the wastefulness of the Palace’s destruction, but were okay to build giant gates to a place that was no longer there? So Sydney, so chic…

This tastefully coloured fountain marks the spot of the Palace’s 210 foot tall dome. I’m surprised that’s not Queen Victoria perched on top.

Timbrol Chemicals/Union Carbide/Residential – Rhodes, NSW

Following on from the Homebush Abattoir is the story of Rhodes, NSW. ‘We’re judged by the company we keep’ has never been truer than in the case of Rhodes, an industrial suburb closely identified with chemicals for most of the 20th century. The winning of the 2000 Olympic Games and subsequent renewal of the former abattoir site at Homebush Bay forced the NSW Government to remediate Rhodes, on the other side of the bay. It was hoped the suburb would be reborn as heavy residential by 2000, but this goal has still not been achieved. The primary reason is this site:

Timbrol was Australia’s first major organic chemical manufacturer, and was established here on Walker Street in 1928. Chemicals manufactured by Timbrol between 1928 and 1957 include chlorine, weed fungicide, and the insecticides DDT and DDE. To commemorate this achievement, a neighbouring street has been named after Timbrol:

In 1957, Timbrol merged with the American chemical concern Union Carbide to form Union Carbide Australia. Union Carbide had a reputation as an innovator within the chemical manufacturing industry. Facing competition from the neighbouring CSR plant, Union Carbide stepped up production of existing chemical products and created many new ones. During the Vietnam War, Union Carbide produced Agent Orange at their Rhodes site.

Whenever Union Carbide would reclaim land from Homebush Bay, it would do so by dumping toxic waste and building over it. This method was extended to the Allied Feeds site further up Walker Street. In 1997, Greenpeace found 36 rusting drums of toxic waste on the former Union Carbide site.

Faced with declining demand, diminishing returns and increasing competition, Union Carbide abandoned its Australian operations entirely in 1985. They were allowed to leave without conducting any kind of cleanup of the Rhodes site. Between 1988 and 1993, the NSW Govt began remediation attempts with the intention of using Rhodes as an Olympic village for the 2000 Sydney Games, but it was only in 2005, with the onset of private residential construction on the sites, did any serious remediation work take place. Many blocks of units were completed between 2005 and 2011, but remained empty as the ongoing cleanup work made the area too toxic to live in. Remediation was completed in early 2011, and construction has resumed.

Homebush Bay remains toxic – swimming and fishing are prohibited, and any fish caught in the bay are too poisonous to eat. The remediation work by Meriton and Thiess and has supposedly made the area safe to live in, but only time will tell.

UPDATE: It’s one year later. Is it safe yet? Find out.