Newsagency/LP & Company Home Products – Campsie, NSW

Beamish Street (above, top left to bottom right) cuts across Campsie like a knife wound, only instead of blood, a spurt of discount stores, fresh produce markets and newsagents has erupted into the populace.

A news-hungry populace. Seriously, there are no fewer than three newsagents active in a very small area here, with at least three more recently departed ones I can recall.

But is it the news, or is it something else these shops provide that has kept them in the Beamish mix when so many others (including McDonald’s – twice!) have dropped out?

Sometimes, my job here is made very easy. The Old Tab Cafe suggests another rarity: the departure of a TAB. Don’t worry, there are still at least three TABs within walking distance of this cafe, but what’s beginning to form is a picture of a suburb that loved to have a punt.

As many nostalgia websites love to remind you, Australia’s suburban demographics are in a constant state of flux. What was is very different to what is, and the habits of the old don’t necessarily appeal to the new.

Campsie is a great example. Originally so Anglo it features an Anglo Road, the suburb is now home to a large Chinese population – and the shops to match.

This former chemist at 235 Beamish tells you all you need to know. In are fried chicken and a dentist (what a combo); out is the passion for the Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs, the area’s beloved NRL team. All that remains to remind us of a more supportive era is a solitary Bulldogs insignia, ravaged by time and weather.

The appeal of Da Doggies may have burned brighter in Campsie’s TAB days, but Chinese gambling habits don’t necessarily align with those of yesterday’s Anglo Campsians. Mahjong and pokies have taken the lead as the preferred way of chasing that elusive jackpot over sports betting or that other friend of the working class, the lottery.

Which brings us to the star of today’s show, 245 Beamish Street.

This site was once home of a Mr John Foreman Watson, who may well have backed winners and losers during his time on earth, which ended right here in October 1954. Eerily, it could be that the paper containing Watson’s obituary was sold at the very place he checked out.

Because here too stood one of Campsie’s many newsagencies (this one with the very no-frills moniker “Newsagency”), now replaced by LP & Company Home Products. Not a Sydney Morning Herald or lotto ball in sight these days.

Or is there?

Shift your perspective and you’ll find Francois Vassiliades did his best to hide the standout feature of this former sweeps station, which now peeks out from behind the ‘sold’ sign.

The Big Lotto Ball’s placement on the shopfront is an instant and arguably unwelcome reminder of a time when the promise of a big win towered over current affairs, and jackpots and bulldogs stood side-by-side just out of reach of the common man.

Cumberland Hotel/TK Plaza – Bankstown, NSW

There isn’t much call for an old English-style hotel pub in Bankstown these days. This particular part of the city, Old Town Plaza, is especially bereft of watering holes thanks to the enormous Bankstown Sports Club around the corner.

Yes, there’s the Bankstown Hotel and the RSL on the other side of the train line, but down here it’s the Sports Club (not to be confused with the Bankstown Sports Hotel nearby), the Oasis Hotel (or the Red Lantern depending on who you ask) or you’re going thirsty.

Those two venues, while fine, are very much products of today’s Bankstown. The Oasis looks like the kind of place you’d hit up to dump some cash into the pokies and have a smoke outside, while the Sports Club has a monopoly on the family friendly crowd. Neither enjoy the kind of maturity conducive to sitting around and making a beer last many hours.

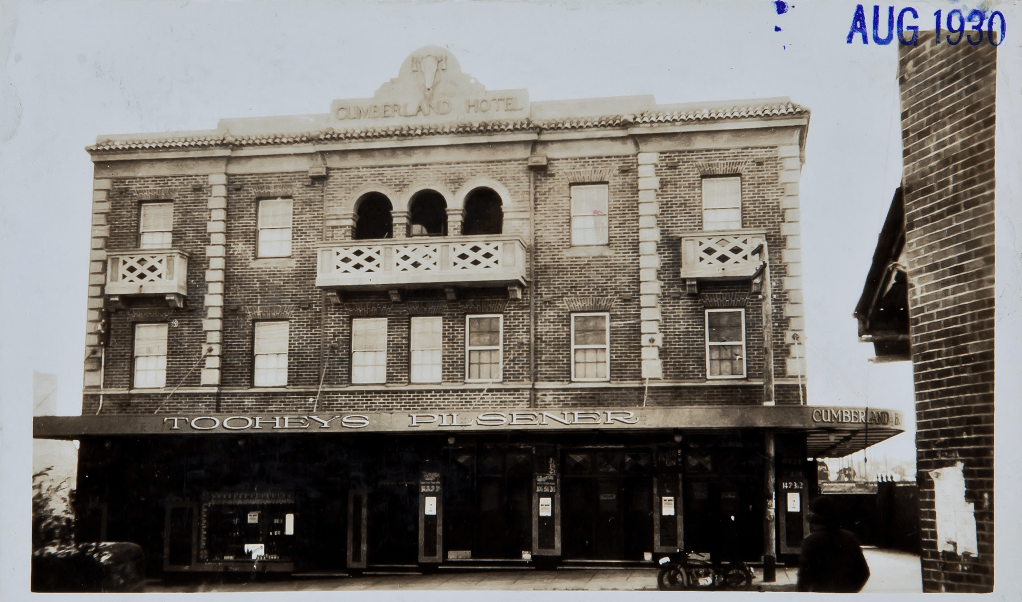

And then there’s the Cumberland Hotel, a proper glimpse into the suburb’s past. If you know Bankstown, you’ll know this venue stands out like the proverbial.

The locals have done their best to incorporate the Cumberland into the street’s mix of fresh food wholesalers, dollar shops and mini marts, but the top half speaks of a time when the working class would need to cool down after a hard day’s work; when a night at the Cumberland might even result in a cheap room upstairs; when Mr. Zhong was still afraid to play with matches.

From what I can gather, the Cumberland has its origins in 1929, when William Hoyes, the licensee of the notorious Rydalmere Hotel, transferred that pub’s licence to his newly purchased hotel in Bankstown. The ruckus at Rydalmere, and Hoyes’ hasty escape, seems to have originated in 1907, when a Dundas policeman disturbed a cadre of dudes drinking illegally – at midday! – at the Catholic Church beside the pub.

For his troubles, Constable Howard was bashed quite severely, but got his own back when he shot at the four pissed louts, injuring one of them. Turns out one of them was the hotel’s licensee, while another was the church’s caretaker. You’d think they could have had a quiet one at the hotel itself, but perhaps they had to wash down a communion wafer.

The incident left its mark on the Rydalmere Hotel to the point where even after 22 years, Hoyes opted to take his licence and start over in a suburb less tarnished by violence… for now.

In 1930, the Cumberland was up and running under the watchful eye of Tooheys. Hoyes made way for O’Regan in 1933, who gave it up to O’Reilly in 1934. The names give a clear indication of Bankstown’s cultural background at the time.

Vincent O’Reilly held onto the Cumberland until 1950, by which time the lay of the land had changed quite a bit. The following year the Cumberland Hotel fell under investigation of the Royal Commission on Liquor, which had put old mate Abe Saffron in the hot seat.

Honest Abe had apparently made some licencing deals with several hotels, including the Cumberland, the Morty in Mortdale and the Civic in Pitt Street, that had not impressed the authorities. At the heart of the matter was the improper funneling of booze between pubs under Saffron’s influence, grossly in breach of the Liquor Act.

While all this was going on, the Cumberland endured another parade of licencees including Mr Kornhauser, Mr Norman, Mr Blair and Mr Geoghegan, the latter of which applied for – and received – a 12-month dancing permit in 1957.

During Geoghegan’s tenure, on a momentous November afternoon, a meeting took place that would change New South Wales’ taxi and golf landscapes permanently.

“In November of 1954, three disgruntled members of Campsie Taxi Drivers Golf Club, while having a drink at the Cumberland Hotel in Bankstown, discussed forming a breakaway group of golfers. It wasn’t until after Melbourne Cup Day of that year that a group of up to 10 cabbies decided to form a Taxi Social Golf Club. The first game was held at East Hills Golf Club on the first Tuesday in January 1955.

The foundation meeting was held that day. A foundation committee was elected and Bankstown Taxi Drivers Golf Club was born. Tuesdays were chosen as golf day because back in those days, they were deemed to be the quietest day of the week for cabbies.”

NSW Taxi Golf Association

There it is, folks. Wonder no more. I shouldn’t think there was too much licenced dancing going on that day.

As the 1960s dawned, things changed even further. Geoghegan was out, and in his wake came Masman, Martin, Conlon, Light, Monkey and a switch to decimal currency.

The Oasis had sprung up around the corner, as had the “Bankstown Bowling Club”. In another sign of the times, a TAB in Fetherstone Street, on the other side of the train line, was seen to be impinging upon the Cumberland’s bread and butter. Blair, Heffernan, Davanzo and Lynch would endure this incursion and take the Cumberland into the 1970s.

The beginning of the end came in the 80s, however, when that old undercurrent of pub violence would again raise its ugly head. By that time, Bankstown had become home to two distinct groups of refugees fleeing overseas wars: Lebanese and Vietnamese. They didn’t always gel.

As is now well understood, youth gang crime became an issue for these two ethnic groups. One night, in July of 1986, tensions boiled over in Bankstown. A brawl started outside Bankstown Station and became so violent that wooden palings were torn from fences to be used as weapons.

It’s not hard to imagine these guys hearing of the brawl during a night at the Cumberland and rushing to the aid of their friends. By then, the Cumberland had become “a seedy old watering hole, with a cast of colourful characters, Viet gangsters being shot on the doorstep, topless barmaids, great beers and lots of laughs”. It couldn’t last.

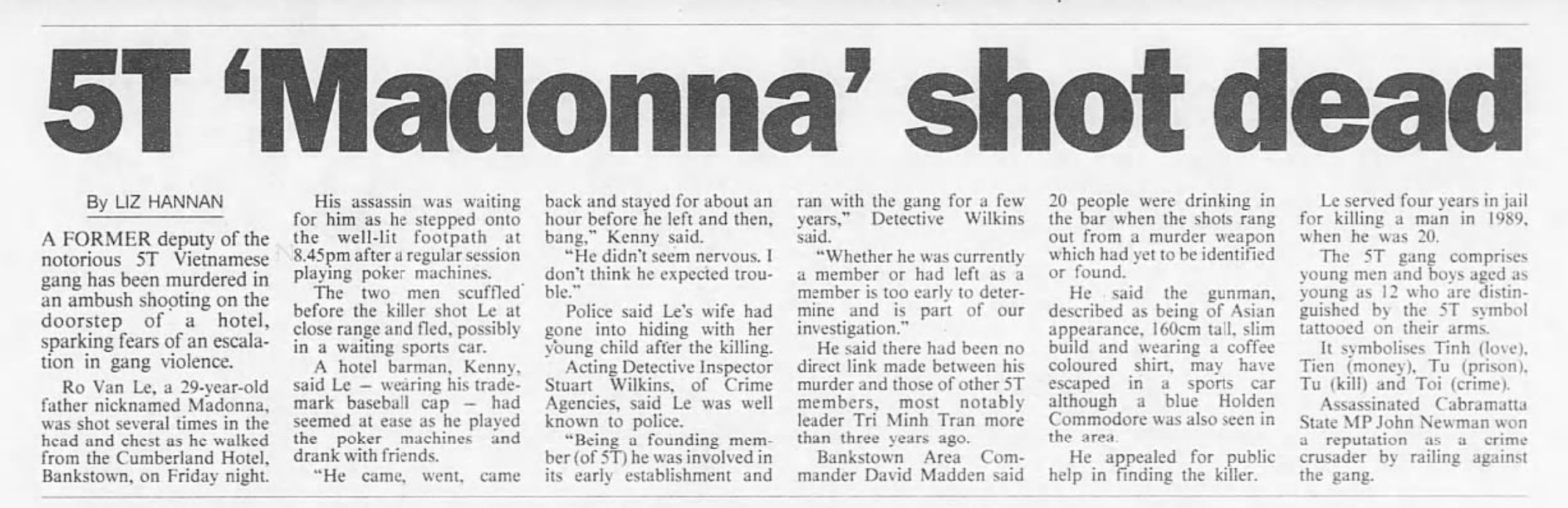

Somehow, the Cumberland staggered into the next decade, which was awash with even more gang violence. Names like 5T and the Madonna Boys should be familiar to anyone who was around at the time. 5T was particularly notorious not only for its violence and clout in the bustling Sydney heroin trade, but for the ridiculous age of its leader, Tri Minh Tran, who took over the gang at 14.

Tran was shot dead in 1995, and gangs such as Red Dragon and the Madonna Boys, led by “Madonna” Ro Van Le, sprung up in the resulting power vacuum. Madonna himself had been convicted of murder in 1989, and a decade later had only just been released from prison when he visited the Cumberland Hotel one Friday night.

It was Madonna’s last. As the drive-by shooter’s bullets entered his head and chest on the footpath outside the Cumberland, they ostensibly ended the hotel as well.

The shooting helped prompt owners Bill and Mario Gravanis to abandon the Cumberland in favour of the Bankstown Sports Hotel further down the road.

Today’s Cumberland is a mix of smaller outlets that have carved up the spacious interior. One must first cross the fruit-laden threshold of TK Plaza…

What was once Madonna’s beloved VIP lounge is likely Skybus Travel, itself no longer in operation if the room full of mangoes and canned squid is anything to go by.

And perhaps the table favoured by those disgruntled cabbie golfers is now a part of Anh Em Quan’s Hot Pot BBQ restaurant. If they’d settled their grievances over a bowl of spicy prawns that day, who knows what kind of world we’d live in now.

Around the back, it’s hard to imagine this was ever a pub. The mural places the Cumberland firmly in the every-second-shop’s-a-fish-market vibe of Old Town Plaza, while the back alley is full of Hiaces rather than getaway cars.

It’s unlikely the Cumberland Hotel will ever serve a cold schooner of beer again. The world that defined the venue is gone. Tooth, Madonna, Constable Howard, the Geoghegans of Bankstown – all are now memories.

At 324, just under the Cumberland’s south wing, the ‘Cumberland Professional Suites’ carry on the name. They probably occupy the rooms upstairs as well, but even they have the sadly familiar For Lease sign outside.

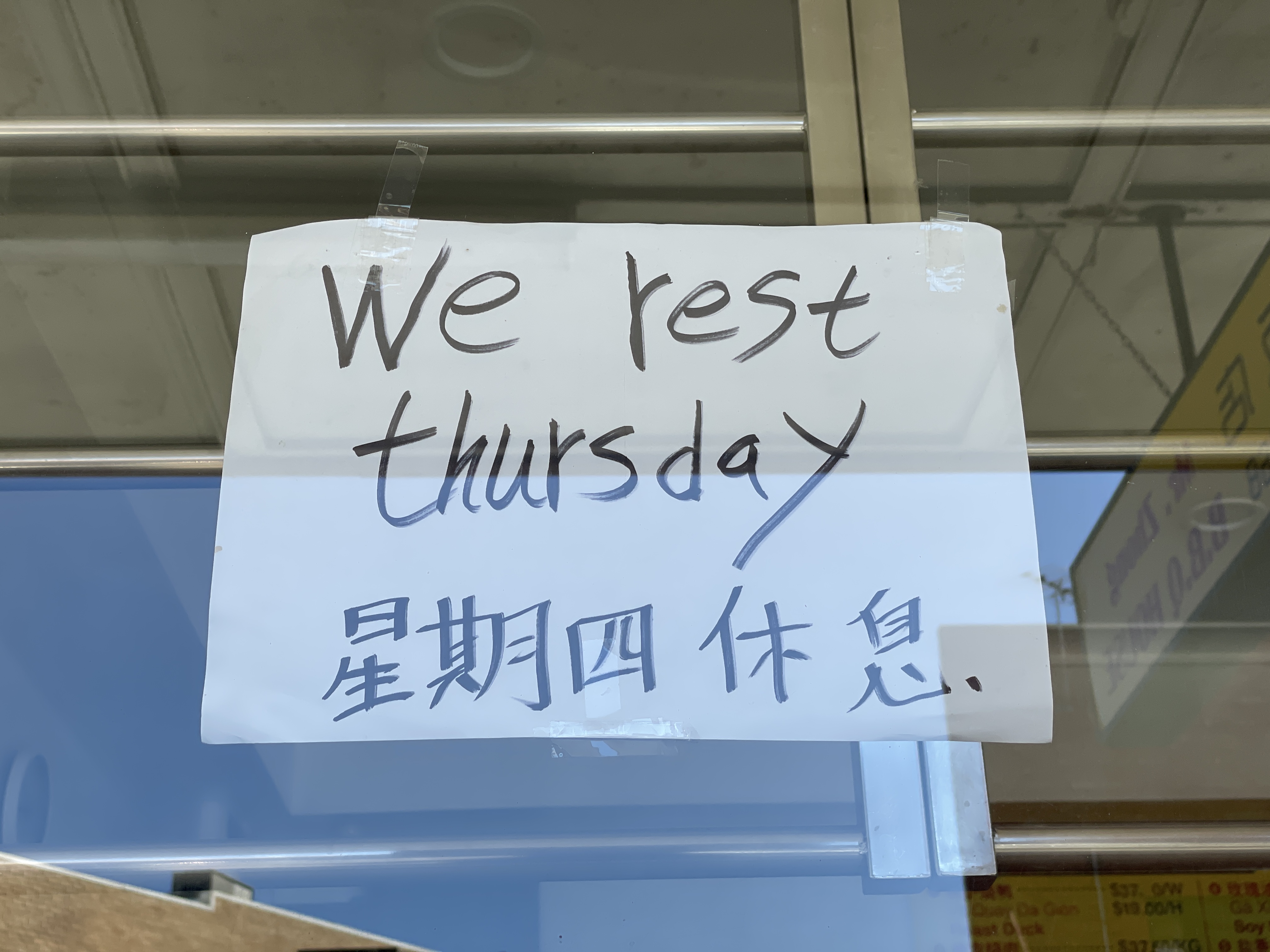

Perhaps the next tenant will take a look at the building’s history and look to maintain some kind of continuity in a way TK and Mr Zhong did not. As I departed fully intact, much to the late Madonna’s envy, I noticed this sign in one of the front windows.

Rest in peace, Cumberland Hotel.

Pizza Hut/Kiddiwinks – Warriewood, NSW

You’ll have to forgive the low-hanging fruit in this case, but when it’s been a while you need a rolling start to get back up to speed.

There’s a certain ballsiness that comes with stepping into Pizza Hut’s red shingled shoes. By inhabiting such a familiar space, you’re inviting comparisons you’re (usually) unable to support. It doesn’t matter whether you’re burying people or educating them – if you’re doing it in an old Pizza Hut, prepare for scrutiny.

When Kiddiwinks, a Northern Beaches childcare centre, accepted the Used To Be A Pizza Hut challenge, it came armed with bold colours and fencing designed to dispel all notions of what had come before.

But what had come before? The Warriewood entertainment precinct had once included all the ingredients for a great (if not fatty) night out: Pizza Hut for dinner, a cinema for a show, a McDonald’s for the car park afterwards and a sewage treatment plant to mask the odour.

That was then. Pizza Hut was the first casualty, going the way of all Huts in the late 90s. By 2008, a dark time at the farthest ebb of all-you-can-eat nostalgia, Warriewood Pizza Hut sat empty and graffiti’d.

This was exactly the kind of visage that screamed potential to the folks at the Hog’s Breath Cafe, who proved a slightly uncomfortable fit into the ‘east coast lite’ feel of Pittwater Road.

Out of breath by 2013, but with an eye-catching green mohawk, the site waited for its next denizen. It was a very long wait indeed; Kiddiwinks wouldn’t sign on the dotted line until 2019 – the furthest east the business has yet ventured.

Another first Kiddiwinks can add to the walls of its “Hampton-style interiors” is that it’s likely the first ever tenant to ever have a menu “approved by NSW Health to meet the recommended daily intake for children”. What a shame then that the kiddis are constantly staring at a burger joint all day long.

Meanwhile, McDonald’s prospered in the absence of competition. So confident is Ronald in this location’s viability that the bare minimum was done to pull the exterior into line with the boxy new Mickey D aesthetic. Going through the drive-thru (or so I’m told) is a journey past the green, angular and dare I say even Hut-like McDonald’s of old.

And perhaps that’s how it should be at a place like this. There needn’t be anything modern about a big block sitting on the curb of a busy arterial road promising flicks and a feed on a Friday night, and steady processing of post-ablutions the rest of the time. On some level even Kiddiwinks knows so, appropriating as it has the old Pizza Hut sign.

Strange bedfellows in every sense.

Toys R Us/Gro Urban Oasis – Miranda, NSW

We spend our lives mourning our childhoods.

Our values and expectations are shaped throughout our younger years, sometimes subconsciously. Once we learn that, say, an ice cream dropped on the hot sand during a day at the beach won’t be replaced, the ice cream becomes a little part of us, a part we can’t get back. As adults we can buy another ice cream, but it’s not the same one. It’s just a band-aid over our initial carelessness, and $5 out of our retirement funds. We still feel the loss.

Every tantrum or outburst we have, every moment of joy, whenever the waterworks spring a leak…that’s a moment when the situation we’ve found adult selves in has touched a nerve from an earlier time. It’s a unique brand of pain we aren’t equipped to handle.

From the 1970s onwards, childhoods became increasingly materialistic. My own was peppered with trips to toy shops and Christmases spent unwrapping action figure after action figure. I never broke an arm climbing trees with Huck and Tom because I was inside on the PlayStation. I never knew that pain and the associated loss of innocence.

But when that PlayStation controller broke, you better believe I felt that.

The values that make the younger generation weep into adulthood are different to the ones who came before (you know, the ones who made it impossible to buy a house). When a brand that played a large part in that childhood dies, it’s a personal attack, even if we hadn’t supported or even thought about that brand for years.

At the (mostly) newly refurbished Westfield Miranda, there’s something new to mourn.

Imagine looking into those gentle brown eyes and telling that face it’s over – he’s insolvent. Imagine being the one to cause that perpetual smile to end. It’d be like pulling the moon from the night sky: the nocturnal world would hate you.

Toys R Us has gone, and there’s an entire generation full of rage at its passing. How could this happen? Don’t toy shops last forever? Where will we take our children when they come of age?

We were there at the beginning, when the American giant arrived on our shores and slew the usurper. When we were invited to meet Barbie, Sonic and Geoffrey, to come in and “have a ball”, to be seduced by wares previously unfathomable to our young eyes.

And we drank deeply.

Never mind that we hadn’t gone in there in years, that we peered inside occasionally and merely wondered why there were so many baby items. Never mind that when we wanted a new board game for game night, we hit up Amazon and their incredible range rather than hiking out to one of many inconvenient locations embedded in mouldy old shopping centres. Never mind that our own children asked for iPads and Xboxes over Barbies and Transformers, and we willingly obliged, even as Hurstville’s double-storey Toys R Us lost an entire floor to Aldi.

We took Geoffrey and his magic factory for granted, and this is the price we paid. We dropped the ice cream, and we’ve done our dash.

Rebel Sport remains – a glimpse into a past when big name retailers could team up and it meant something – but the toy story is over at Miranda. The threshold that saw so many delighted kids quivering with anticipation, birthday money firmly – but not too firmly – clutched in tiny digits, has been sealed up and replaced with an ad for a shop elsewhere in the centre.

Imagine the scene behind this wall. A big empty space that, once upon a time, someone saw so much promise in. “This place could make kids happy,” they thought. And it could, until it couldn’t. Today, that possibility has been restored.

Downstairs, just a bit away from the escalator that once elevated us to a place where we didn’t have to grow up, is this sign overlooked by Westfield’s image consultants.

The quotations around the R sometimes appear in official Toys R Us signage, and sometimes they don’t. Here they seem to be a disclaimer, as though whoever crafted the sign didn’t quite believe the claim behind the name: that “toys were them”.

It’s certainly true today.