Rozelle Theatre/Arch Stone & Residential – Rozelle, NSW

Whoa, deja vu! This incarnation of the Rozelle Theatre, constructed in 1927, was actually the second theatre to be built at this location. You can take one look at it and know it was a job by architect Charles Bohringer, who also brought us the Homebush Theatre. That Bohringer…it’s like he was tortured by this single vision in his head and could never quite exorcise it, no matter how many theatres he designed.

While we’re on the topic of torture, Zero Dark Thirty’s got nothing on Miss Louise Mack, who sadistically inflicted a series of lectures on children at the theatre during the late 1920s:

You won’t be surprised to learn that it was Hoyts who played the part of the executioner in the tragic tale of this theatre, which ceased projection in 1960 – and speaking of executions:

After an embarrassing stint as a function centre, the cinema today stands as an Arch Stone tile outlet topped with an apartment block. It’d be a damn spooky place to live, too…it’s said that on a dark and stormy night, you can still hear the yawns of Miss Mack’s students…

NSWFB Fire Station/Kiama Community Arts Centre – Kiama, NSW

Known locally as ‘the old fire station’, Kiama’s community arts centre is home to Daisy, the Decorated Dairy Cow. Since 1991, Daisy’s coat of paint has changed whenever a new exhibition is on at the centre, with the current design (above) being particularly clever.

Known locally as ‘the old fire station’, Kiama’s community arts centre is home to Daisy, the Decorated Dairy Cow. Since 1991, Daisy’s coat of paint has changed whenever a new exhibition is on at the centre, with the current design (above) being particularly clever.

It’s a far cry from the Kiama of 1899, which was decimated by a great fire that destroyed 15 buildings due to lack of a fire brigade. Yep, that’ll do it. Let’s just hope no fires break out in Kiama now…it would be an udder tragedy (I’M SO SORRY).

St. James Theatre/Beverly Hills Cinemas – Beverly Hills, NSW

Let’s cut to the chase: the Beverly Hills Cinemas are looking a little…porky these days. It’s hard not to notice the expanding waistline anymore, even for the sake of politeness. What I’m saying is, if the Beverly Hills Cinemas were a person, they’d need to take the Kayla Itsines challenge a few times to squeeze back into those trackpants.

Let’s cut to the chase: the Beverly Hills Cinemas are looking a little…porky these days. It’s hard not to notice the expanding waistline anymore, even for the sake of politeness. What I’m saying is, if the Beverly Hills Cinemas were a person, they’d need to take the Kayla Itsines challenge a few times to squeeze back into those trackpants.

But it wasn’t always this way. Back before the cinema was built, the suburb was known as Dumbleton, after a nearby farm. The opening of the Dumbleton train station in 1931 had opened up the suburb to the rest of Sydney in a way the previous public transport option – a coach service from Hurstville station – had not.

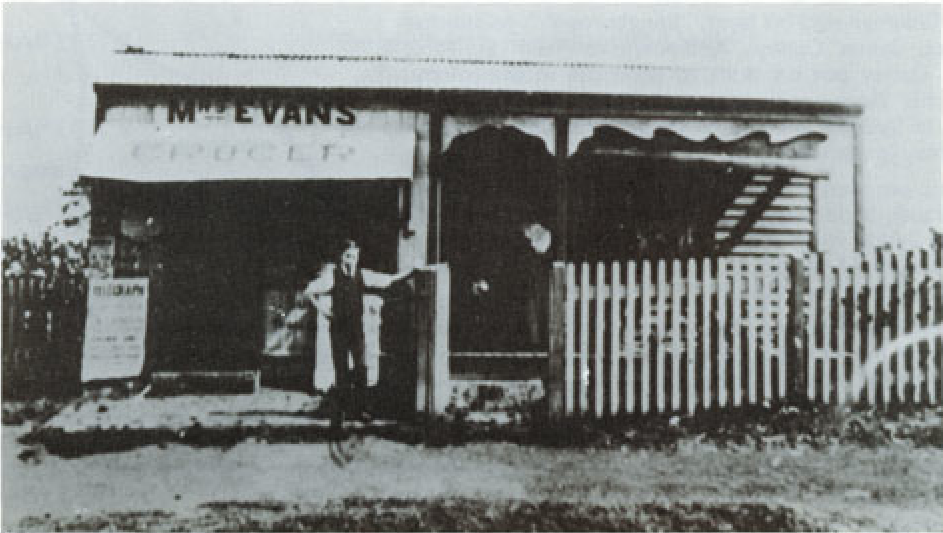

Dumbleton’s first shop had only opened in 1908 (on the site of the present day Beverly Hills Hotel), so there wasn’t exactly a major reason to go there. Dumbleton residents hoped to change this in 1910, when a post office was opened within the existing store. It was like the proto-Westfield.

The Second World War brought military personnel to Dumbleton, further increasing its population and forcing it to come up with more shops to keep people entertained, but it’s kinda hard to make anything entertaining when your suburb’s name is Dumbleton.

In late 1938, plans began for a picture theatre along King Georges Road with a projected completion date of 1940. I suppose the Dumbletonians were hoping to emulate the success of the Savoy theatre in nearby Hurstville, but they still had the nagging problem of that name.

An American cultural influence had been building in the outskirts of Sydney with the advent of cinema, so with an impending theatre and the belief that the USA would soon be joining the war effort, a move was made in 1940 to change the suburb’s name to the much more glamourous sounding Beverly Hills – Hollywood on the East Hills line. The Californian equivalent was home to famous movie stars, and with the completion of the St. James Theatre later that year, so would Dumbleton.

Dumbleton bites the dust as the St. James (centre left) gives rise to Beverly Hills, 1940. Image courtesy Georges River Libraries

A strip of palm trees down the centre of King Georges Road was added to complement the Hollywood theme in a move no one in the 1940s could have predicted would become so tacky by the present day.

St. James Theatre looking very much like a bank, 1966. Image courtesy Georges River Libraries

The St. James Theatre entertained the residents of the growing suburb (even those older residents who had loudly complained about the name change) for decades until the 1970s, when the voracious Hoyts incorporated it into its suburban chain.

Inside the St. James Theatre, 1981. Image courtesy Georges River Libraries

By 1978, it had fallen into disrepair like many of its suburban cousins that had survived the mass demolition of such cinemas during the progressive 60s, and was showing adult films. Saint James indeed.

St. James Theatre lobby, 1980. Image courtesy Georges River Libraries

It was that year when developer Jim Tsagias bought the St. James, with plans to transform it into a function centre. Something changed his mind (perhaps the palm trees) and he decided to restore it as a cinema.

The final reel of St. James Theatre, 1982. Image courtesy Georges River Libraries

In 1982 it was reopened as the one-screen Beverly Hills Cinema, and in 1983 it was converted to a twin.

Seeing double at Beverly Hills Twin Cinema, 1983. Image courtesy Georges River Libraries

And couldn’t you tell. For years, the bigger Cinema No. 1 would play host to the big budget blockbusters, while smaller, more intimate pictures or films late in their run were relegated to the tiny Cinema No. 2, which had been shoehorned in above the first. It was an awkward setup, but one that built a reputation as the cheapest cinema in Sydney (based on ticket prices, of course), and became one of the most popular family venues in the south west, especially when coupled with the nearby Beverly Hills Pizza Hut. Movies then all-you-can-eat pizza: it doesn’t get much more 90s than that.

The cinema was looking a bit dated by the early 2000s, but not as bad as the bank next door (originally a Bank of NSW, later a Westpac). Sandwiched between the cinema and the Pizza Hut was one of so many suburban bank branches closed during that time, and it sat dormant for many years just like the Hut.

Perhaps realising it wasn’t a good look, and that there was an opportunity to expand, the Tsagias family bought the bank in 2004 and moved in, creating a video arcade in the new space which greatly relieved pressure from the cramped waiting area.

But this wasn’t enough. In 2008, a complete redevelopment saw the Beverly Hills upgraded to a six-screen cinema. The derelict Pizza Hut was cut in half to make room for more screens and a mini-power station, and the entire facade facing King Georges Road was given the facelift (in true Beverly Hills fashion) that it sports today.

Not quite the case around the back, though.

From the alley behind the cinema, it’s easy to see the layout of the original St James and the bank next door. The structure on the extreme left is new, and sits on the Pizza Hut’s territory. The Pizza Hut recently vanished from existence, perhaps to make way for more parking for the cinema, or a new restaurant (just what BH needs). Whenever you see extensive renovations going on, it’s usually a safe bet that it’s being done to prepare the property for sale. Sure enough, the Tsagias family placed the Beverly Hills Cinema on the market late last year. It seems as if Event Cinemas has taken control, at least of the screening coordination, but it remains to be seen if the Beverly Hills will remain a cinema under a new owner.

If it doesn’t, they may have to change the suburb’s name again.

Commonwealth Banking Corporation/Commonwealth Bank – Enmore, NSW

In 1991, the Commonwealth Bank had a brainwave: “Everyone hates big business, so let’s sound less like one.” And so ended over 30 years of the Commonwealth Banking Corporation, which gave way to the kinder, warmer Commonwealth Bank we know today.

The reality is that in 1959, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia split into two entities; one good (Reserve Bank of Australia), and one pure evil (the Commonwealth Banking Corporation). And no, changing your name back hasn’t fooled anyone, CBA.